The AAPG/Datapages Combined Publications Database

AAPG Bulletin

Full Text

![]() Click to view page images in PDF format.

Click to view page images in PDF format.

AAPG Bulletin, V.

DOI: 10.1306/01282523103

Cretaceous sequence stratigraphy and gross depositional environments, Browse Basin, Australia: Implications for the extent of petroleum systems and plays

Stephen T. Abbott,1 Emmanuelle Grosjean,2 Dianne Edwards,3 Nadege Rollet,4 Tehani Palu,5 and Megan E. Lech6

1Basin Systems Branch, Geoscience Australia, Canberra, Australia; [email protected]

2Basin Systems Branch, Geoscience Australia, Canberra, Australia; [email protected]

3Basin Systems Branch, Geoscience Australia, Canberra, Australia; [email protected]

4Basin Systems Branch, Geoscience Australia, Canberra, Australia; [email protected]

5Basin Systems Branch, Geoscience Australia, Canberra, Australia; [email protected]

6Retired; [email protected]

ABSTRACT

The Cretaceous fill of the Browse Basin hosts the producing Ichthys-Prelude gas field and several subeconomic gas and oil fields. Using two-dimensional seismic surveys and 31 wells, and an approach that integrates the interpretation of gross depositional environments (GDEs) within a sequence stratigraphic framework, the aim of this basin-scale study was to determine stratigraphic relationships between (and distribution of) source, reservoir, and seal petroleum play elements. Third-order clinoform sequences in the Browse Cretaceous succession are grouped into three supersequences made up of platform, slope, basin-floor, and submarine fan GDEs. First-order thermal and tectono-eustatic accommodation was modulated by plate tectonic and epeirogenic movements associated with the breakup of southeastern Gondwana. However, intrabasinal evidence for a tectonic control on accommodation (e.g., angularity at sequence boundaries) is rare. The hierarchical stacking of GDEs, and hence source, reservoir, and seal play elements, provides context for the three petroleum systems that exist in the Browse Cretaceous succession. This sequence stratigraphic architecture predicts the extent of plays and petroleum systems in areas of the basin that are untested by drilling.

INTRODUCTION

The Browse Basin (Figure 1) lies within the North West Shelf region of Australia. Exploration commenced in 1967 and has yielded numerous, mainly gas, hydrocarbon accumulations (Figure 2A). Proved and probable reserves for the Browse Basin are estimated at 514 million bbl (3022 petajoules [PJ]) of oil and natural gas liquids and 13.96 TCF (15,701 PJ) of gas (Geoscience Australia, 2023). First production was in 2018, with liquefied petroleum gas and condensate from the Ichthys-Prelude accumulation.

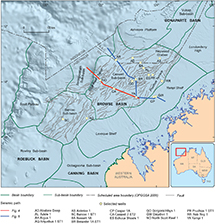

Figure 1.

Browse Basin location, structural elements, selected wells, and seismic paths for Figures 4 and 5. NSW = New South Wales; NT = Northern Territory; QLD = Queensland; SA = South Australia; TAS = Tasmania; VIC = Victoria; WA = Western Australia.

Figure 1.

Browse Basin location, structural elements, selected wells, and seismic paths for Figures 4 and 5. NSW = New South Wales; NT = Northern Territory; QLD = Queensland; SA = South Australia; TAS = Tasmania; VIC = Victoria; WA = Western Australia.

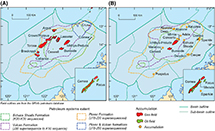

Figure 2.

(A) Browse Basin hydrocarbon accumulations and mapped extent of petroleum systems. (B) Hydrocarbon accumulations and petroleum systems that include at least one Cretaceous reservoir. Petroleum systems extents are adapted from Palu et al. (2017a). Field outlines are adapted from the GPInfo petroleum database (gpinfo.com.au).

Figure 2.

(A) Browse Basin hydrocarbon accumulations and mapped extent of petroleum systems. (B) Hydrocarbon accumulations and petroleum systems that include at least one Cretaceous reservoir. Petroleum systems extents are adapted from Palu et al. (2017a). Field outlines are adapted from the GPInfo petroleum database (gpinfo.com.au).

Reservoir intervals within 18 Browse Basin hydrocarbon accumulations are of Cretaceous age (Figure 2B). The Brewster Member (Berriasian) forms part of the Ichthys-Prelude field and is the only Cretaceous reservoir in production. The Heywood Formation, Jamieson Formation, Asterias Member, and Fenelon Formation (Barremian–Campanian) are host to uneconomic oil accumulations (e.g., Cornea field).

The Cretaceous sedimentary succession in the Browse Basin, referred to here as the Browse Cretaceous succession, comprises seismically imaged clinoform sequences that were deposited during a thermal subsidence phase of basin evolution. This paper is based on a basin-scale two-dimensional (2-D) seismic mapping program of the Browse Cretaceous succession that updates Blevin et al. (1998b) by extending and infilling horizon mapping and refining the sequence stratigraphic framework. Clinoform stratal geometry, together with well data, have been used to predict the basin-wide distribution of platform, slope, basin-floor, and submarine fan gross depositional environments (GDEs), and therefore the distribution of source, reservoir, and seal hydrocarbon play elements. This work provides sequence stratigraphic and GDE context for hydrocarbon plays that include a Cretaceous reservoir and gives increased confidence in predicting the extent of the petroleum systems in the Browse Cretaceous succession.

REGIONAL GEOLOGIC SETTING

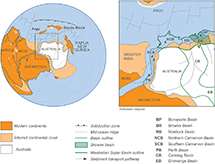

Westralian Super Basin

The Browse Basin is one of five extensional basins that comprise the Westralian Super Basin (Bradshaw et al., 1988). Extension commenced during the late Carboniferous–early Permian as part of the East Gondwana Interior rift (e.g., Haig et al., 2017). A passive margin along the outboard margin of the Westralian Super Basin was established after the separation of the Cimmerian continent (early Permian), Banda and Argo continental fragments (both in the Late Jurassic), and Greater India (Valanginian) (Gibbons et al., 2012; Hall, 2012; Metcalfe, 2013). The regional paleogeographic setting of the Westralian Super Basin during the Aptian (Figure 3) coincides with the Cretaceous maximum inundation of the Australian continent (Frakes et al., 1987). At this time, the Westralian Super Basin may have been contiguous with the intracratonic Canning and Eromanga Basins. Deposition in the Browse Basin was effectively terminated by Middle–Late Miocene inversion caused by the collision of the Australian plate with Eurasia (Keep and Moss, 2000).

Figure 3.

Aptian paleogeographic setting of the Westralian Super Basin, including the Browse Basin. Sediment transport pathways are inferred from U-Pb geochronology and provenance analysis. Modified from Lewis and Sircombe (2013).

Figure 3.

Aptian paleogeographic setting of the Westralian Super Basin, including the Browse Basin. Sediment transport pathways are inferred from U-Pb geochronology and provenance analysis. Modified from Lewis and Sircombe (2013).

Browse Basin

The tectonostratigraphic evolution of the Browse Basin is divided into six basin phases that were influenced by the plate tectonic history of the Westralian Super Basin (Struckmeyer et al., 1998): (1) late Carboniferous–early Permian extension linked to development of the East Gondwana Interior rift, (2) late Permian to Late Triassic thermal subsidence, (3) Late Triassic to Early Jurassic Inversion, (4) Early to Middle Jurassic extension linked to separation of the Argo continental fragment, (5) Late Jurassic to Middle Miocene thermal subsidence, and (6) Middle to Late Miocene inversion linked to the collision of the Australian plate with Eurasia. The subject of this paper, the Cretaceous succession (Figure 4), forms part of basin phase 5.

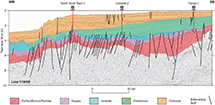

Figure 4.

Interpreted seismic line through the Caswell Sub-basin showing principal tectonostratigraphic units and extensional faults. The Browse Cretaceous succession (green) was deposited during a phase of thermal basin subsidence. See Figure 1 for seismic line location.

Figure 4.

Interpreted seismic line through the Caswell Sub-basin showing principal tectonostratigraphic units and extensional faults. The Browse Cretaceous succession (green) was deposited during a phase of thermal basin subsidence. See Figure 1 for seismic line location.

Browse Basin structural elements referred to in the text are depicted in Figure 1. The Caswell and Barcoo Sub-basins are the main depocenters and contain Paleozoic to Cenozoic successions more than 15 and 12 km thick, respectively. These depocenters are located over the East Gondwana Interior rift and have persisted as the main Browse Basin depocenters throughout the Late Jurassic–Middle Miocene thermal subsidence phase. The Scott Reef trend is one of several faulted structural highs located within the Barcoo and Caswell Sub-basins that were formed by the reactivation of Paleozoic faults during the Late Triassic inversion (Struckmeyer et al., 1998; Keep and Moss, 2000).

The Yampi and Leveque (structural) shelves are regions of gently dipping Proterozoic basement overlain by a relatively thin basin succession. Outboard of these structural shelf areas, the fault-bounded Prudhoe terrace dips toward the Caswell and Barcoo depocenters. The Scott plateau and Seringapatam Sub-basin comprise the outboard elements of the Browse Basin. These areas contain up to 3 km of Mesozoic–Cenozoic strata (Stagg and Exon, 1981).

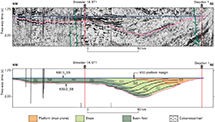

Browse Cretaceous Succession

The Cretaceous succession in the Browse Basin (Figures 4, 5) reaches a maximum thickness of approximately 3000 and 2000 m in the Caswell and Barcoo Sub-basins, respectively. Inboard, the succession thins over the Prudhoe terrace and Yampi and Leveque (structural) shelves, where it onlaps Proterozoic basement. Outboard, the Browse Cretaceous succession thins and downlaps Jurassic basement. Over the Seringapatam Sub-basin and Scott plateau, Cretaceous strata have been mapped as a veneer of inferred deep marine sediments (Stagg and Exon, 1981).

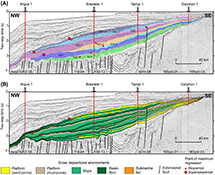

Figure 5.

Interpreted seismic path through the Caswell Sub-basin highlighting the Browse Cretaceous succession. (A) Sequence stratigraphic subdivision and nomenclature. (B) Gross depositional environments. See Figure 1 for seismic path location.

Figure 5.

Interpreted seismic path through the Caswell Sub-basin highlighting the Browse Cretaceous succession. (A) Sequence stratigraphic subdivision and nomenclature. (B) Gross depositional environments. See Figure 1 for seismic path location.

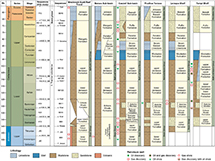

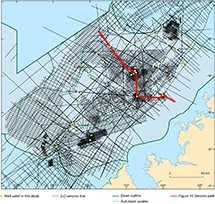

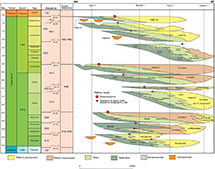

The stratigraphy of the Browse Cretaceous succession is presented in Figure 6. Lithology is dominated by marine mudstone that is punctuated by relatively thin sandstone-prone intervals. Other lithologies include marl, calcilutite, and carbonaceous mudstone. The sequence stratigraphic framework for this study (Figure 6; Table 1) is from Blevin et al. (1998b), and the sequence stratigraphic nomenclature of Marshall and Lang (2013) has been applied to promote consistent terminology across the Westralian Super Basin. Lithostratigraphic names used herein are from the Australian Stratigraphic Units Database (ASUD; Geoscience Australia and Australian Stratigraphy Commission, 2017). Lithostratigraphic names used by petroleum exploration companies but not listed in the ASUD are denoted by inverted commas.

Figure 6.

Stratigraphic chart of the Browse Cretaceous succession (updated excerpt from the chart by Kelman et al. 2017) showing regional sequence stratigraphic framework, tectonic history, lithostratigraphy, and hydrocarbon shows. Biostratigraphic zonations used to date sequence boundaries are adapted from Kelman et al. (2017), which are calibrated to the 2016 Geologic Time Scale (Ogg et al., 2016). *Sequence framework of Blevin et al. (1998b). Grp = Group; Jkimm = Jurassic (Kimmeridgian); Jtith = Jurassic (Tithonian); Kalb1 = Cretaceous (Albian 1); Kalb2 = Cretaceous (Albian 2); Kapt = Cretaceous (Aptian); Kbar = Cretaceous (Barremian); Kbase = base Cretaceous; Kecamp = Cretaceous (early Campanian); Kmaas = Cretaceous (Maastrichtian); Ktur = Cretaceous (Turonian); Kval = Cretaceous (Valanginian); Lst = Limestone; Tbase = base Cenozoic; Tpal = Cenozoic (Paleocene). Note: Asterias Member is synonymous with M. australis Member.

Figure 6.

Stratigraphic chart of the Browse Cretaceous succession (updated excerpt from the chart by Kelman et al. 2017) showing regional sequence stratigraphic framework, tectonic history, lithostratigraphy, and hydrocarbon shows. Biostratigraphic zonations used to date sequence boundaries are adapted from Kelman et al. (2017), which are calibrated to the 2016 Geologic Time Scale (Ogg et al., 2016). *Sequence framework of Blevin et al. (1998b). Grp = Group; Jkimm = Jurassic (Kimmeridgian); Jtith = Jurassic (Tithonian); Kalb1 = Cretaceous (Albian 1); Kalb2 = Cretaceous (Albian 2); Kapt = Cretaceous (Aptian); Kbar = Cretaceous (Barremian); Kbase = base Cretaceous; Kecamp = Cretaceous (early Campanian); Kmaas = Cretaceous (Maastrichtian); Ktur = Cretaceous (Turonian); Kval = Cretaceous (Valanginian); Lst = Limestone; Tbase = base Cenozoic; Tpal = Cenozoic (Paleocene). Note: Asterias Member is synonymous with M. australis Member.

Petroleum Systems

Four Mesozoic petroleum systems linked to three lithostratigraphic source rock intervals have been identified in the Browse Basin (Grosjean et al., 2015; Le Poidevin et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2016; Palu et al., 2017b). The extent of these petroleum systems, based on the geochemistry of crude oils and natural gases, is shown in Figure 2A.

The fluvial-deltaic Plover Formation (Lower–Middle Jurassic) contains abundant terrestrial organic matter, has charged gas accumulations across the Caswell Sub-basin, and has been recognized as the source of the gas component in the Cretaceous reservoired accumulations of the Yampi shelf (Grosjean et al., 2016; Palu et al., 2017b; Spaak et al., 2020). The marine Vulcan Formation (Jurassic–Cretaceous) includes terrestrial and marine organic matter and has generated gas and liquids across the central Caswell Sub-basin, including gas charge to the Ichthys-Prelude and Burnside accumulations. The marine mudstone Echuca Shoals Formation (Lower Cretaceous) contains marine and terrestrial organic matter; is the source of the oil component of the Cornea, Gwydion, and Sparkle accumulations on the Yampi shelf; and is the primary source of the Caswell oil accumulation in the southern Caswell Sub-basin. A fourth petroleum system is represented by fluids recovered from the Crux field of the Heywood graben, which have a geochemical signature distinct from all other fluids in the Browse Basin. The hydrocarbons in Crux are thought to be locally derived from terrestrial source rocks present within the thick Jurassic sequences of the Heywood graben and encompassing Plover and Vulcan Formations (Spaak et al., 2020). Modeling by Palu et al. (2017b) indicates that hydrocarbon expulsion from source rocks in the Caswell Sub-basin commenced in the Late Cretaceous and that in the Barcoo Sub-basin, expulsion has mostly been limited to the Plover source rock.

In this paper, a hydrocarbon accumulation, as defined by Le Poidevin et al. (2015, Appendix A), is “a general term representing all concentrations of petroleum irrespective of their commercial potential.” An accumulation may comprise single or multiple petroleum pools all grouped on, or related to, the same individual geological structure and/or stratigraphic position. Accumulations that include Cretaceous reservoirs are shown in Figure 2B. The only commercially important Cretaceous reservoir is the Brewster Member, which forms part of the Ichthys-Prelude gas field in the central Caswell Sub-basin. Subeconomic oil accumulations are limited to the central Caswell Sub-basin (Caswell) and the Yampi shelf (Cornea, Gwydion). The Echuca Shoals, lower Heywood, upper Heywood, and Jamieson Formations (Figure 6) together are regarded as the regional hydrocarbon seal, whereas other seals are intraformational (Le Poidevin et al., 2015).

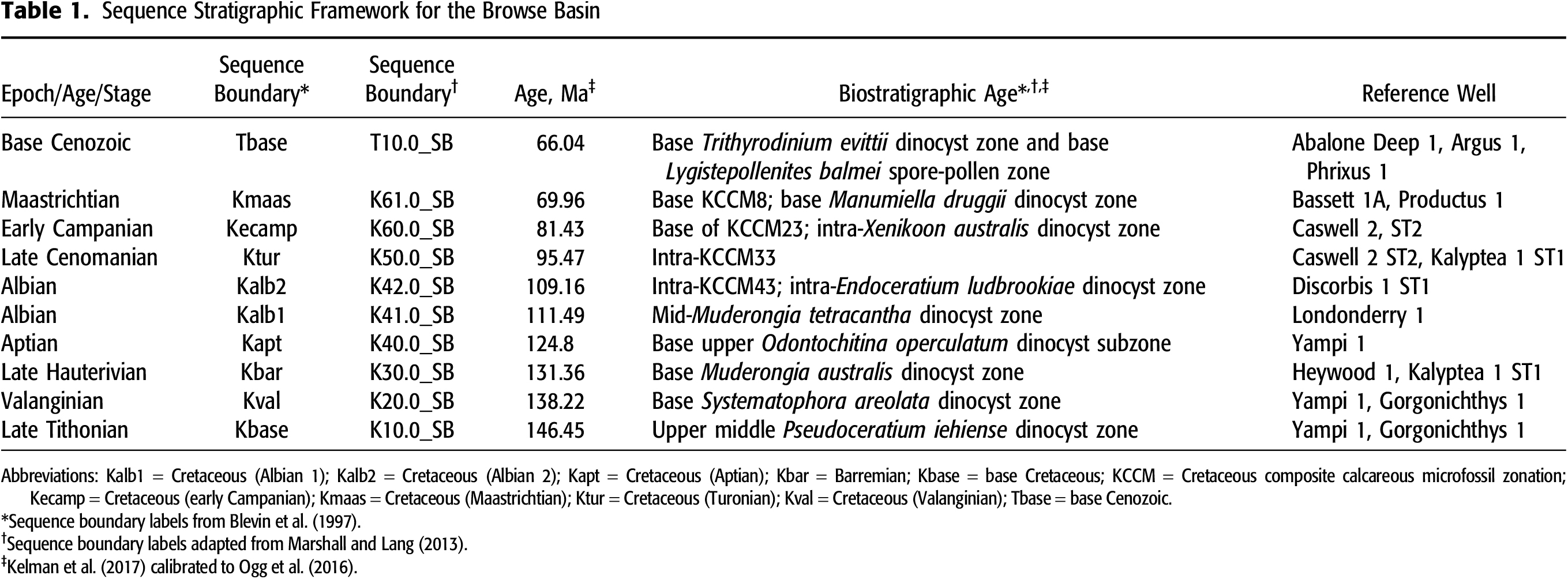

DATA

The Browse Basin is covered by two-dimensional (2-D) and three-dimensional (3-D) seismic surveys of variable vintage, quality, two-way time record length, and orientation. Twenty-six 2-D seismic surveys (Figure 7) were interpreted to complete basin-wide horizon mapping, supplemented by minor interpretation of selected 3-D surveys in areas where 2-D seismic coverage is lacking or of poor quality. Survey information is tabulated in Rollet et al. (2016a). The generally fair-to-poor quality of the 2-D seismic data is a function of the pre-1990 vintage of some surveys and the loss of resolution caused by the overlying carbonate-rich Cenozoic strata. Depth-converted grids of the seismic surfaces mapped in this study are available as a digital data set (Rollet et al., 2019).

Figure 7.

Browse Basin two-dimensional (2-D) seismic surveys and wells used in this study. Also shown is the seismic path for Figure 10.

Figure 7.

Browse Basin two-dimensional (2-D) seismic surveys and wells used in this study. Also shown is the seismic path for Figure 10.

Thirty-one wells were analyzed to constrain seismic horizon mapping and to characterize GDEs. Composite well logs for wells used in this study were compiled by Rollet et al. (2016a, appendix C). The well composite logs include a suite of wire-line logs (including gamma ray), synthetic seismograms generated from check shot–calibrated wire-line sonic log data, lithology (based mainly on drill cuttings), organic geochemistry (including total organic carbon [TOC]) and biostratigraphic data extracted from Geoscience Australia’s STRATDAT database. Biostratigraphic zonation (based mainly on palynology for the Cretaceous interval) and absolute ages of sequence boundaries (Table 1) are from the chart by Kelman et al. (2017).

METHODOLOGY AND TERMINOLOGY

Seismic Sequence Stratigraphy

The Browse Cretaceous succession has been subdivided into nine sequences (sensu Catuneanu et al., 2009) that are imaged in the regional 2-D seismic grid. These sequences, referred to as clinoform sequences hereafter, are analogous to the transgressive-regressive (T-R) sequence of Embry and Johannessen (1993, figure 5) or the genetic sequence of Galloway (1989, figure 3) in which progradational clinoform successions predominate over much thinner transgressive and condensed intervals. The terminology applied to clinoform sequences in this paper is summarized in Figure 8A. As a pragmatic approach to basin-scale mapping using 2-D seismic surveys of variable quality, sequence boundaries are defined as seismic reflections that bound clinoform sequences. Sequence boundaries so defined represent stratigraphic intervals several tens of meters thick and incorporate transgressive and condensed strata. Outboard, sequence boundaries are associated with regional downlap. Inboard, sequence boundaries occur in the context of onlap. Angular stratal relationships across sequence boundaries are rare.

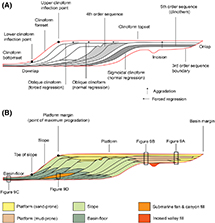

Figure 8.

Sequence stratigraphic and gross depositional environment (GDE) terminology used in this study. (A) Sequence hierarchy and clinoform geometry. (B) Arrangement of GDEs within a clinoform sequence. The topological positions of the GDEs illustrated in Figure 9 are indicated.

Figure 8.

Sequence stratigraphic and gross depositional environment (GDE) terminology used in this study. (A) Sequence hierarchy and clinoform geometry. (B) Arrangement of GDEs within a clinoform sequence. The topological positions of the GDEs illustrated in Figure 9 are indicated.

At the clinoform sequence scale, sequence boundaries are analogous to the maximum regressive surface of Embry (2010) and the maximum progradation surface of Emery and Myers (1996). Transgressive strata are generally too thin to be resolved in 2-D seismic surveys, such that Browse Cretaceous sequence boundaries also incorporate maximum flooding and subaerial erosion surfaces (sensu Catuneanu et al., 2009). For sequences that include submarine fans and associated incisions, sequence boundaries are mapped under the submarine fans as in van Wagoner et al. (1990, figure 19). Normal regressive and forced regressive clinoform geometries (Helland-Hansen and Martinsen, 1996) are recognized in some clinoform sequences. The codification of sequence and sequence boundary names (Figure 6) follows Marshall and Lang (2013). For example, K10.0_SB is the basal sequence boundary of the K10 clinoform sequence. Sequence boundaries referred to herein are sequence bases, unless otherwise indicated.

Clinoform sequences are regarded as the fundamental sequence in the sequence stratigraphic hierarchy of the Browse Cretaceous succession because these are the units recognized in the 2-D seismic grid that can be regionally mapped. Clinoform sequences are third-order sequences in the sequence stratigraphic hierarchy used herein. Second-order sequences (referred to as supersequences) comprise two or more clinoform sequences. The Browse Cretaceous succession is part of the first-order thermal subsidence basin phase. In some clinoform sequences, fourth-order sequences are locally resolved in 2-D seismic profiles, whereas individual clinoform reflections are considered fifth-order sequences (i.e., clinothems).

GDEs and GDE Maps

Sequence stratigraphic models predict a relationship between clinoform segments and the distribution of GDEs (e.g., Vail, 1987). Clinoform topsets incorporate coastal plain, shoreline, and shelf depositional environments. Foreset and bottomset clinoform segments represent slope and basin-floor depositional systems, respectively. Sangree and Widmier (1977, p. 165) observed that the threefold subdivision of clinoforms “provides a useful gross subdivision for classification and interpretation of seismic facies units” (see also Hubbard et al., 1985). We accordingly recognize platform, slope, and basin-floor GDEs, and we also distinguish submarine fan GDEs (Figure 8B). Each GDE is made up of one or more depositional environments. The term “depositional environment” is used here in the sense of Boggs (2001). Following Glorstad-Clark et al. (2010), the term “platform,” instead of shelf, is used to distinguish clinoform topsets in an effectively intracratonic setting, such as Browse Cretaceous sequences (Figures 4, 5), from those that pass beyond a shelf break into the deep ocean (e.g., modern passive margin).

The GDEs are further characterized by lithology and gamma-ray log motif (Figure 9). Lithological information is derived from published well composites (Rollet et al., 2016a) and well completion reports. Lithology is based on drill cutting descriptions (rarely core), which typically include observations on composition, grain size, sorting, and environmentally informative components such as plant debris, glauconite, microcrystalline carbonate, and biogenic silica. The TOC information is derived from the TOC track on well composite logs and publications such as that of Boreham et al. (1997). Wire-line log (principally gamma) motifs (Figure 9E) provide insight into trends of lithological variation and hence depositional environment (e.g., Emery and Myers, 1996).

Figure 9.

Browse Cretaceous succession gross depositional environments (GDEs). (A) Yampi 1, (B) Echuca Shoals 1, (C) Caswell 2 ST2, and (D) Bassett 1A. (E) Schematic relationship between gamma-ray (GR) log motifs (terminology adapted from Emery and Myers, 1996), lithology, and GDE classification. See Figure 1 for well locations. MD = measured depth.

Figure 9.

Browse Cretaceous succession gross depositional environments (GDEs). (A) Yampi 1, (B) Echuca Shoals 1, (C) Caswell 2 ST2, and (D) Bassett 1A. (E) Schematic relationship between gamma-ray (GR) log motifs (terminology adapted from Emery and Myers, 1996), lithology, and GDE classification. See Figure 1 for well locations. MD = measured depth.

The GDE maps for each clinoform sequence have been constructed by identifying clinoform inflection points (Figure 8A) on sequence boundaries in seismic profiles across the basin. In map view, the line that connects upper clinoform inflection points between interpreted seismic profiles (i.e., platform margin) is the boundary between platform and slope GDEs. The platform margin on an upper sequence boundary is also the point of maximum progradation. Similarly, the line that connects lower clinoform inflection points (i.e., toe of slope) marks the boundary between slope and basin-floor GDEs. Polygons defined by these boundaries show the distribution of GDEs for each clinoform sequence at the time of maximum progradation. Submarine fan polygons are envelopes around the seismically defined limits of submarine fan complexes.

GDEs

Platform

The platform GDE comprises clinoform topset successions made up of siliciclastic sandstone and mudstone in varying proportions. Sandstones are mostly fine grained but are locally coarse grained, especially toward the inboard basin margin. Glauconite is a common accessory mineral, and coal interbeds are present in some Upper Cretaceous well intersections. Clinoform topset successions represent stacked fourth- and fifth-order sequences.

Sand-prone platform GDE (Figures 8B, 9A) are typically associated with oblique clinoforms and both normal-regressive and forced-regressive clinoform geometries. Lithology is dominated by sandstone. Stacked sandstone units exhibiting blocky gamma-log trends (Figure 9A, E) are prominent. In some wells, the sandstones are coarse grained, with coal fragments present as an accessory. This combination of features in a clinoform topset context indicates the contribution of fluvial environments to the sand-prone platform GDE. Sandier-upward lithology trends, funnel-shaped gamma-log motifs (Figure 9A, E), fine- to medium-grained sand texture, and the presence of glauconite indicate marginal- to shallow-marine environments. In the sand-prone platform GDE, T-R transits of the shoreline distribute sand-rich facies across the entire platform.

Mud-prone platform GDEs are typically associated with sigmoidal clinoforms and normal progradation (Figure 8B). The mud-prone platform GDE is distinguished by siltstone and claystone successions, with up to approximately 20% sandstone in units up to approximately 10 m thick (Figure 9B). Sandstone units, if present, may display funnel gamma motifs, indicative of marginal- and shallow-marine environments. The mud-rich successions transition into sand-prone platform GDE (Figure 8B) toward the inboard basin margin, except in cases where the latter has been removed by erosion. In general, only partial T-R transits of the platform occurred during the development of mud-prone platform GDE, resulting in a transition between sand-prone (i.e., proximal) and mud-prone (i.e., distal) platform environments.

Slope and Basin-Floor

The slope and basin-floor GDEs (Figures 8B; 9A–D) are generally dominated by siliciclastic claystone but commonly include carbonate-rich lithologies such as calcareous mudstone, marl, or micrite (e.g., Figure 9C). Biogenic silica and elevated TOC content are also observed in some occurrences.

Samples from the Browse Cretaceous succession that have been analyzed for source rock properties yield TOC values of mostly between 1% and 2%, with maximum values of approximately 10% (Blevin et al., 1998a). These authors determined a relationship between source rock properties (inclusive of elevated TOC) and peak flooding intervals; examples illustrated in their well-log plots from the Discorbis 1, Kalyptea 1, and Caswell 2 wells correspond to the slope and basin-floor GDE of this study. Silica enrichment is noted from some occurrences of the slope and basin-floor GDE and is prominent in the lower Jamieson Formation (Figure 6). The radiolarite origin of the silica in the Windalia Radiolarite, a correlate of the lower Jamieson Formation in the Northern Carnarvon Basin, was documented by Hocking et al. (1987).

The concentration of nonsiliciclastic components indicates low rates of deposition within the clinoform slope and basin-floor settings. Beyond the toe of slope, the basin-floor GDE represents condensed sections in which fine-grained carbonate lithologies may dominate (Figures 8B, 9C). In situations in which a mudstone slope GDE is overlain by a carbonate-rich basin-floor GDE, a prominent uphole gamma-log excursion toward lower gAPI values is observed (e.g., Figure 9C).

Submarine Fan

The submarine fan GDE comprises sharp-based sandstone bodies interbedded with mudstone, marl, and micrite, and is typically expressed as a blocky gamma-ray log signature (Figure 9D, E). Submarine fan sandstones are variably fine to coarse grained and commonly glauconitic. In seismic profiles, fan systems are distinguished by mounded stratal geometries within a toe-of-slope and basin-floor context (Figure 8B). In some examples, fan complexes and their proximal incised valleys or canyons can be mapped in seismic profiles and depicted on paleogeographic maps. Stacking of submarine fan GDE within and across clinoform sequences suggests the reoccupation of long-standing incised valley and canyon depositional systems.

CLINOFORM SEQUENCES

Clinoform sequences mapped across the regional 2-D seismic grid are grouped into three supersequences (Figure 10). Figure 11 depicts the distribution of GDEs within sequences at their respective times of maximum progradation, and isochore maps of each interval are shown in Figure 12A–G. Figure 12H is an isochore map of the entire Browse Cretaceous succession that highlights the Caswell Sub-basin as the main Cretaceous depocenter. Figures 13–18 are representative dip-oriented seismic cross sections of each clinoform sequence. Sequence boundaries (e.g., K10.0_SB) are sequence bases (Table 1). Named structural elements (e.g., basins, sub-basins) referred to in the text can be found in Figures 1 and 3.

Figure 10.

Wheeler chart for the Browse Cretaceous succession. See Figure 7 for the interpreted seismic path used to construct the chart. Fm = Formation; Mbr = Member.

Figure 10.

Wheeler chart for the Browse Cretaceous succession. See Figure 7 for the interpreted seismic path used to construct the chart. Fm = Formation; Mbr = Member.

Figure 11.

Gross depositional environments of Browse Cretaceous sequences and supersequences at the time of maximum progradation. (A) K10 sequence. (B) K20 sequence. (C) K30 sequence. (D) K40 sequence. (E) K50 sequence. (F) K60.0 sequence. (G) K61.0 sequence. Seismic paths for Figures 13–18 are indicated. WA = Western Australia.

Figure 11.

Gross depositional environments of Browse Cretaceous sequences and supersequences at the time of maximum progradation. (A) K10 sequence. (B) K20 sequence. (C) K30 sequence. (D) K40 sequence. (E) K50 sequence. (F) K60.0 sequence. (G) K61.0 sequence. Seismic paths for Figures 13–18 are indicated. WA = Western Australia.

Figure 12.

Isochore maps of Browse Cretaceous sequences, supersequences, and the entire Cretaceous succession. (A) K10 sequence. (B) K20 sequence. (C) K30 sequence. (D) K40 sequence. (E) K50 sequence. (F) K60.0 sequence. (G) K61.0 sequence. (H) Browse Cretaceous succession.

Figure 12.

Isochore maps of Browse Cretaceous sequences, supersequences, and the entire Cretaceous succession. (A) K10 sequence. (B) K20 sequence. (C) K30 sequence. (D) K40 sequence. (E) K50 sequence. (F) K60.0 sequence. (G) K61.0 sequence. (H) Browse Cretaceous succession.

K10–K30 Supersequence

K10 Sequence

The K10 sequence boundary (K10.0_SB) in wells is typically expressed at inboard locations by an abrupt up-section lithology shift from mudstone to sandstone and a large and abrupt negative gamma-log excursion (Figure 9A). In seismic profiles, this surface is locally expressed as a high-amplitude reflection, and across the outboard basin is a regional downlap surface. At some locations along the inboard basin margin, the K10.0_SB rests on Proterozoic basement. The K10 sequence (Figure 13) is characterized by sand-prone platform facies and oblique clinoforms. Normal regressive clinoform geometry dominates forced regressive geometry. In some dip profiles, the K10 sequence includes up to five fourth-order sequences (Figure 13). At the time of maximum progradation (Figure 11A), deltaic complexes extended into the southern Caswell Sub-basin and the adjacent Oobagooma Sub-basin of the Canning Basin, and these correspond to the position of K10 depocenters (Figure 12A). Clinoform dips in seismic strike lines (e.g., bbhr-14) indicate a northeasterly component of K10 progradation.

Figure 13.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K10 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11A for location). The profile is flattened on the K20.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Figure 13.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K10 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11A for location). The profile is flattened on the K20.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Interpretation

The sand-dominated platform GDE prevailed throughout K10 deposition and developed under mostly normal regressive and aggradational conditions. Some fourth-order sequences are the product of forced regression and indicate periods of relative sea-level fall. The deltaic complex within the Oobagooma Sub-basin, as interpreted from the arcuate shape of the basinward platform GDE boundary, implies a contribution to sediment delivery from a Canning Basin drainage system. A Canning Basin sediment source is also indicated by a northeasterly component of progradation across the Leveque shelf (Figure 1). These observations are consistent with a U-Pb zircon geochronology study (Lewis and Sircombe, 2013) that indicates Mesoproterozoic zircons sampled from K10 sandstones are sourced from the Musgrave Province in the Canning Basin hinterland. Although sequence stratigraphic models predict the presence of submarine fan GDE in sequences with sandy topsets (e.g., Steel and Olsen, 2002), especially under conditions of forced regression, submarine fan GDEs are not recognized in the regional 2-D seismic surveys investigated in this study.

K20 Sequence

The K20 sequence boundary (K20.0_SB) is characterized in wells at most locations by a transition from K10 sand-prone platform GDE to K20 basin-floor mudstone GDE (Figure 9A), but it is a sandstone-on-sandstone contact along the inboard basin margin. Outboard, K20.0_SB is expressed as a regional downlap surface. In Yampi 1 (Figure 14), this surface is overlain by a 2-m conglomeratic interval. The platform GDE in the K20 sequence is predominantly mud-prone (Figure 11B). Sand-prone platform sediments are confined to the basin margin, where an onlapping relationship is observed with the rugose Proterozoic basement. The K20 clinoforms are sigmoidal in character (Figure 14) and strongly aggradational. Slope and basin-floor GDEs are dominated by siliciclastic mudstone and are calcareous in some wells.

Figure 14.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K20 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11B for location). The profile is flattened on the K30.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Figure 14.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K20 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11B for location). The profile is flattened on the K30.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

The main K20 depocenter lies mostly over the inner Caswell Sub-basin, where it bifurcates around a pre-Cretaceous structural high into the Barcoo Sub-basin (Figure 12B). A structural high also separates the main depocenter from a secondary depocenter in the northcentral Caswell Sub-basin. In Figure 14, fourth-order sequences are seen to step progressively outboard, but the youngest of these are stacked in the main Caswell depocenter. A northeasterly component of K20 progradation is indicated by apparent clinoform dips in seismic lines that trend along basin strike.

Interpretation

The K20 sequence prograded to a point of maximum regression beyond the underlying K10 platform margin. Sand-prone platform sediments were confined to the inboard basin margin. A sand-prone lobe in the Oobagooma Sub-basin (Figure 11B), together with northeasterly dipping clinoforms, imply a continued contribution of sediment from the Canning Basin. The K20 thickness was strongly influenced by antecedent structural highs, and in the main K20 depocenter, a higher rate of accommodation resulted in stacking of the youngest K20 fourth-order sequences.

K30 Sequence

The K30 sequence boundary (K30.0_SB) is subtle in wells over much of its distribution due to the continuity of mudstone and claystone across the boundary (Figure 9B). It is a regional downlap surface outboard and an onlap surface along the inboard basin margin. Local erosion at K30.0_SB, expressed by the truncation of underlying reflections, is observed in the area around Yampi 1 (Figure 15). The K30 sequence (Figure 15) is similar in facies composition and clinoform geometry to K20. In particular, facies are mud-prone, except along the inboard basin margin, where sand-prone platform facies consist of stacked sandstone units. Slope and basin-floor mudstone is calcareous in some well intersections, and in the outer Barcoo Sub-basin, includes marl. In some wells, basin-floor facies include fine carbonaceous fragments.

Figure 15.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K30 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11C for location). The profile is flattened on the K40.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Figure 15.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K30 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11C for location). The profile is flattened on the K40.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

The main K30 depocenter lies in the Caswell Sub-basin, where it is divided by an east-northeast–trending structural high (Figure 12C). The K30 platform margin prograded into the basin to a point of maximum progradation outboard of the terminal K20 platform margin (Figure 11C). Several discrete sand-rich bodies have been mapped locally within the K30 sequence (Figure 11C), such as those present in Asterias 1 and Adele 1 in the northeastern Caswell Sub-basin.

Interpretation

As the K30 sequence prograded into the basin, sand-prone platform facies onlapped the inboard basin margin. The K30 sequence thus continued the onlapping, aggradational, and transgressive character of the K10–K30 supersequence (Figure 10). As for K20, the main K30 sequence depocenter developed on either side of a pre-Cretaceous structural high. Several discrete sandstone bodies identified within areas of poor seismic resolution have been identified tentatively as submarine fans.

K40 Supersequence

K40.0–K42.0 Sequences

The K40 sequence boundary (K40.0_SB) at the base of the K40 supersequence is marked in some inboard wells by an abrupt up-section shift from mudstone to sandstone and a corresponding change to lower gamma-log values. Outboard, the sequence boundary is mostly a mudstone-on-mudstone contact (e.g., Echuca Shoals 1; Figure 9B). The K40.0_SB is mapped on a high amplitude reflection inboard but is expressed as a regional downlap surface in the Caswell and Barcoo Sub-basins. In the main Caswell Sub-basin depocenter, the K40 supersequence is subdivided into the K40.0, K41.0, and K42.0 clinoform sequences (Figures 10, 16).

Figure 16.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K40 supersequence (see Figure 11D for location). The profile is flattened on the K50.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Figure 16.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K40 supersequence (see Figure 11D for location). The profile is flattened on the K50.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Platform GDEs within the K40 supersequence are predominantly mud-prone, and clinoform geometry is generally sigmoidal and aggradational. However, the K40.0 sequence is distinguished by a sand-prone platform (“D. davidii sand,” based on Diconodinium davidii) that extends to a point of maximum progradation in the central Caswell Sub-basin (Figures 11D, 16). Sand-prone platform GDEs onlap and aggrade against the inboard basin margin. The K40 slope and basin-floor GDEs are commonly calcareous and variably siliceous.

The K40 depocenter occupies most of the Caswell and Barcoo Sub-basins but is divided by a northeasterly trending structural high (Figure 12D). At the time of maximum K40 progradation and the culmination of the K40 supersequence (Figure 10), the platform margin had progressed to the outboard margins of the Caswell and Barcoo Sub-basins (Figure 11D). Despite the overall progradational character of the K40 supersequence, constituent K40.0, K41.0, and K42.0 sequences are stacked in the inner Caswell depocenter.

Interpretation

Initial deposition of the K40 sequence represents a marked landward shift in facies (Figure 10). The K40 supersequence is similar in character to the K10–K30 supersequence in that it is dominated by sequences containing extensive mud-prone platform facies and by the confinement of sandy platform facies to the inboard basin margin. As for the K20 sequence, stacking of the K40.0, K41.0, and K42.0 clinoform sequences (rather than basinward accretion) within the inner Caswell depocenter indicates that accommodation rates in this area were relatively high. Nonetheless, by the time of K40 maximum progradation, the Caswell and Barcoo depocenters were filled, and progradation had progressed into the Seringapatam Sub-basin and Ashmore platform.

The siliceous nature of the K40 basin-floor GDE has been documented throughout the Westralian Super Basin (e.g., Windalia Radiolarite; Romine et al., 1997), and these authors have related the siliceous facies to the development of open oceanic circulation and the upwelling of currents, rich in oxygen and radiolarite-derived silica, as Greater India drifted away from Australia (e.g., Bradshaw et al., 1988). Regional biogenic silica enrichment is also consistent with prolonged and widespread condensed deposition associated with the K40.0_SB second-order sequence boundary. The Australian continental inundation Cretaceous maximum occurred in the mid-Aptian (Frakes et al., 1987; Struckmeyer and Brown, 1990), and this event may be linked to K40.0_SB. At this time, much of the Australian continent was covered by shallow seas, including a marine connection to the Westralian Super Basin via the Canning Basin (Figure 3).

K50–K60 Supersequence

K50 Sequence

In wells, the K50 sequence boundary (K50.0_SB) is distinguished by an up-section increase in carbonate content, abrupt at some locations, within an overall fine-grained succession (e.g., calcareous mudstone to calcilutite in Caswell 2 ST2; Figure 9C). Gamma-ray logs show a corresponding shift to lower values. The K50.0_SB corresponds to a high-amplitude reflection and regional downlap surface across most of its distribution. The diminutive K50 clinoform sequence is dominated by variably calcareous mudstone, micrite, and marl (Figures 10, 17). Its depocenter lies in the inner Caswell Sub-basin (Figure 12E), where clinoforms dip away from the depocenter to the northeast and southwest along strike-oriented seismic lines. Deep incision of the K50 sequence is widespread (Figure 10), resulting in the variable preservation of the K50 depocenter (Figure 12E).

Figure 17.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K50 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11E for location). The profile is flattened on the K60.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Figure 17.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K50 clinoform sequence (see Figure 11E for location). The profile is flattened on the K60.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

A mud-prone platform GDE extends across the Yampi and Leveque shelves (Figure 11E), whereas to the northeast, on the Londonderry high (Figure 1), Pattillo and Nicholls (1990) described glauconitic sandstone from several well intersections. The slope GDE consists of siliciclastic mudstone or mixtures of siliciclastic mudstone, micrite, and marl. Basin floor sediments are dominated by fine-grained carbonate in some wells (e.g., Caswell 2 ST2; Figure 9C). In the northern Caswell Sub-basin, intervals of very fine-grained, glauconitic sandstone, typically 5–10 m thick, occur within the K50 basin-floor succession.

Interpretation

Second-order marine flooding across the basal K50 sequence boundary (Figure 10) was followed by progradation of the K50 sequence across the Yampi and Leveque structural shelves and into the Caswell Sub-basin. Along dip-oriented seismic lines clinoforms dip toward the northeast and southwest, away from the K50 depocenter, indicating sediment supply from the Caswell hinterland. The calcareous composition of the K50 clinoform sequence implies starvation of siliciclastic sediment that occurred during maximum transgression of the Browse Cretaceous succession (Figure 10). Shallow-marine sands, such as those seen on the Londonderry high, were deposited along the basin margin but were subsequently removed by erosion along the Browse Basin segment of the Westralian Super Basin. Intervals of very-fine-grained glauconitic sandstone located in the K50 basin-floor facies in the northeastern Caswell sub-basin are enigmatic. They may represent small-scale submarine fan development or may have been deposited by fourth- or fifth-order shoreline transits.

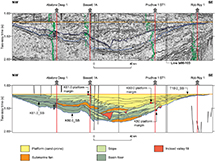

K60.0 Sequence

The basal K60.0 sequence boundary (K60.0_SB) is expressed in seismic profiles as a regional downlap surface across the outboard basin. Inboard, deep and extensive incision occurs at the sequence boundary (Figures 11F, 18). Incision at K60.0_SB is also locally evident across the outboard Caswell and Barcoo Sub-basins. The K60.0 clinoform sequence marks a return to platform-wide sand-prone GDEs within the Browse Cretaceous succession and, for the first time, extensive development of submarine fan GDEs. Normal regressive, aggradational clinoform geometries are dominant. At maximum progradation, the sandy platform extended into the K60.0 depocenter in the Central Caswell Sub-basin (Figure 12F). In seismic lines oriented along depositional strike, apparent clinoform dips indicate progradation away from the depocenter toward the northeast and southwest. Deltaic lobes are evident along the platform margin, and submarine fans are present in the northeastern Caswell Sub-basin (Figure 11F). Large and extensive incision systems have been mapped (Figure 11F), and although most prominent at the basal sequence boundary, they are also recognized within the K60.0 succession.

Figure 18.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K60.0 and K61.0 clinoform sequences (see Figure 11F, G for location). The profile is flattened on the T10.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Figure 18.

Interpreted seismic profile for the K60.0 and K61.0 clinoform sequences (see Figure 11F, G for location). The profile is flattened on the T10.0_SB sequence boundary. Note that vertical exaggeration makes faults appear vertical.

Interpretation

Regional base-level fall at the K60.0_SB resulted in locally deep incision into the underlying K50 sequence (Figure 10) associated with incised valley and submarine canyon systems. The K60.0 sequence prograded into the basin as a complex of fluvio-deltaic lobes, and a northeasterly and southwesterly component of progradation indicates a sediment source from the Caswell hinterland. Sediments were captured by incised valley and canyon systems that fed the submarine fans on the basin-floor.

K61.0 Sequence

The K61.0 sequence boundary (K61.0_SB) is a moderate- to high-amplitude seismic reflection over the outboard basin, where it is a regional downlap surface over K60.0 and K50 basin-floor deposits. At locations where the sequence boundary is overlain by a submarine fan complex (e.g., Bassett 1A; Figure 9D) the abrupt lithological change to sand-rich facies is accompanied by an abrupt up-section shift to lower gamma-ray log values. Inboard, the sequence boundary incises the K60.0 sequence.

The K61.0 sequence represents a continuation of the K60.0 facies composition and sequence architecture, including incision at the basal sequence boundary (K61.0_SB), sand-prone platform facies that extended to the platform margin, and incision systems linked to submarine fan complexes (Figures 11G, 18). At the point of maximum progradation, the K61.0 platform reached its widest extent in the Caswell Sub-basin depocenter. On seismic lines oriented along basin-strike, K61.0 clinoforms dip to the northeast. Within the K61.0 depocenter, three submarine fan complexes are recognized (Figure 11G).

Interpretation

The K61.0 sequence is a continuation of the style of sequence development that shaped the K60.0 sequence. The K61.0 sequence prograded as a complex of deltaic lobes outboard and to the northeast into the Caswell Sub-basin (Figure 11G). The main sediment source continued to be the Caswell hinterland. At maximum progradation, the K61.0 sequence stepped outboard of K60.0 and represents the culmination of the K50–K60 supersequence.

DISCUSSION

Accommodation History

The Cretaceous succession in the Browse Basin was deposited during a thermal subsidence phase (i.e., basin phase 5) of basin evolution. Thermal subsidence commenced with the late Tithonian separation of Argo and concluded at the mid-Miocene inversion. In the Northern Carnarvon Basin, however, the onset of thermal subsidence was delayed by the synrift stage (early Berriasian–early Valanginian) of Greater India separation (Figure 3), and this tectonic activity influenced deposition of the K10 and K20 sequences in the Browse Basin. Despite the overall thermal subsidence setting of the Browse Cretaceous succession, several regional seismic stratigraphic studies across the Westralian Super Basin (Pattillo and Nicholls, 1990; Romine et al., 1997; Blevin et al., 1998b; Smith et al., 1999; Longley et al., 2002) emphasize plate tectonic movements associated with the breakup of southeastern Gondwana (e.g., breakup and separation of Greater India, Antarctica, and smaller continental fragments from Australia) as the main driver of sequence development. In the following, we review and assess the controls on accommodation for the Browse Cretaceous succession with reference to the hierarchical arrangement of clinoform sequences depicted in Figure 10.

First-Order Accommodation

Sequence stacking and distribution of GDEs within the Browse Cretaceous succession describe a first-order T-R trend with a Turonian peak (Figure 10). The first-order transgressive trend commenced with K10 deposition, when the sand-prone platform margin (i.e., the contemporary shoreline) was located in an outboard position (Figure 11A). Younger sequences onlapped the basin margin, and a transgressive trend is expressed by back-stepping of sand-prone platform GDEs (Figure 11B–D). Transgression culminated at a Turonian first-order transgressive peak (Figure 11E). For the K60.0 and K61.0 sequences, platform-wide, sand-prone GDEs prograded into the basin (Figure 11F, G), completing the first-order T-R trend.

The overall T-R architecture of the Browse Cretaceous succession is consistent with the thermal subsidence curves for basin phase 5 modeled by Kennard et al. (2004). These curves show that after the onset of seafloor spreading between Argo and the Browse Basin, thermal subsidence was initially rapid, consistent with the Lower Cretaceous transgressive trend. Subsidence began to wane in the Turonian, leading to the Upper Cretaceous regressive trend. The Cretaceous tectono-eustatic trend (Haq, 2014) also peaked in the Turonian. Tectono-eustasy and thermal subsidence combined to produce the first-order sequence that includes the entire Browse Cretaceous succession.

Second- and Third-Order Accommodation

The K10-K30 supersequence (Figure 10) consists of three stacked clinoform sequences that transgress the basin margin in a landward direction and prograde basinward. The basal K10.0 supersequence boundary marks the onset of rifting between Australia and Greater India in the Northern Carnarvon Basin and deposition of the immense Barrow Delta system in extensional sub-basins (Ross and Vail, 1994; Paumard et al., 2018). The sand-prone K10 sequence in the Browse Basin is the distal equivalent of the Barrow Delta system. The K10 deltaic complex in the Roebuck Basin (Figure 11A) and northerly dipping clinoforms observed in strike-oriented seismic lines in the Browse Basin indicate that sediment supply was at least partly delivered to the Browse Basin via the Canning Basin. The K20.0 sequence boundary is regarded as the breakup unconformity marking the separation of Greater India from the Northern Carnarvon Basin (e.g., Marshall and Lang, 2013) and has been mapped across the entire Westralian Super Basin. This surface is disconformable throughout its distribution in the Westralian Super Basin, although an angular unconformity is locally developed over structural “arches” in the Northern Carnarvon Basin (Tindale et al., 1998). The K10 and K20 sequences in the Browse Basin are confidently linked to the plate tectonic process occurring in the Northern Carnarvon Basin. We also note that the age of breakup (i.e., oldest oceanic crust) between Greater India and Antarctica (Direen, 2012) brackets the age of the K30.0 sequence boundary.

The K40.0 sequence boundary is a major flooding interval (Figure 10). The overlying K40 supersequence comprises three clinoform sequences that together continue the Early Cretaceous transgressive trend in a landward direction, whereas outboard, each sequence prograded progressively further into the basin. The K40.0 disconformity has been mapped across the Westralian Super Basin (Marshall and Lang, 2013). The age of the K40.0 surface lies within the Aptian peak in the Cretaceous marine inundation of the Australian continent (Frakes et al., 1987; Struckmeyer and Brown, 1990). This transgression and inundation of approximately half of the Australian continent has been ascribed to poorly understood continent-scale tectonic movement (Struckmeyer and Brown, 1990; Russell and Gurnis, 1994).

The K50.0 supersequence-bounding surface marks the transgressive peak of the Browse Cretaceous succession. The three clinoform sequences that make up the overlying K50–K60 supersequence describe a regressive trend in the inboard basin. Outboard, the clinoform sequences prograded progressively further into the basin. In the late Turonian, uplift along the western edge of the Australian continent had commenced and continued into the Maastrichtian (Russell and Gurnis, 1994). In the Browse and Bonaparte Basins, this uplift may have led to the Campanian base-level fall that resulted in widespread incision at the K60.0 sequence boundary (Figure 10). Epeirogenic uplift also may have contributed to an increase in sediment supply from the hinterland and forced regression of the K50–K60 supersequence during waning thermal subsidence.

An important intrabasin influence on second-, third-, and higher-order accommodations in the Browse Basin was differential subsidence over antecedent structural highs. These highs are corridors of extensional faulting inherited from Paleozoic horsts and graben that trend along the northeast-southwest structural grain of the basin which, at some locations, are modified by Triassic inversion (Struckmeyer et al., 1998). Pronounced thickness variations over these highs are evident in dip-oriented cross sections and isochore maps of the K20 and K30 sequences, as well as the K40 supersequence (Figures 12, 14–16). Accommodation is influenced to the extent that third-order and higher-order sequences are stacked in depocenters between structural highs instead of accreted to the edge of the outboard contemporary platform margin.

Hydrocarbon Play Elements, Accumulations, and Plays

Source Rocks

The source rocks affiliated with Browse Cretaceous hydrocarbon accumulations are summarized in Table 2. For mudstone and marl samples from the Browse Cretaceous succession, Boreham et al. (1997) presented plots of initial source rock quality (i.e., S2 versus %TOC before maturation). The majority of samples from the K10, K20, and K30 sequences were assessed as fair to good source rock quality, whereas samples from K40 were assessed as poor or fair. The samples from the K50 and K60 sequences yielded poor source rock quality. Source rock characteristics for the Echuca Shoals Formation (K20–K30 sequences) have been reevaluated using an updated compilation of TOC and Rock-Eval pyrolysis data (Palu et al., 2017a). This reassessment confirmed that the hydrocarbon-generating potential of the K20 and K30 sequences is only fair. Small-angle neutron scattering analyses, which detect the presence of generated bitumen and mobile hydrocarbons in pores, have shown that the oil generated by Echuca Shoals Formation source rocks has not been expelled due to insufficient oil saturation. It has been suggested that the mobilization and transport of Echuca Shoals–sourced oil into Cretaceous reservoirs of the Yampi shelf have been assisted by the migration of Plover-sourced gas (Palu et al., 2017a, b).

Blevin et al. (1998a, b) integrated the geochemical results from Boreham et al. (1997) with their sequence stratigraphic framework and recognized a relationship between marine source rocks and condensed section conditions associated with maximum flooding and downlap. In the Caswell 2 well, for example, source rock intervals were identified at the bases of the K20 and K30 sequences, as well as the K40 supersequence. Using high gamma-log values as a proxy for TOC composition, Kennard et al. (2004) broadened the mapped distribution of potential source rock intervals using wells that lacked geochemical data.

Proven and potential marine source rocks occur within the basin-floor GDE of this study. The distribution of potential source rocks can be mapped using seismic sequence characteristics, refined according to the availability of downhole geochemical and well-log data, and extrapolated in areas with poor seismic or well control. Using this approach in a reconnaissance study, Rollet et al. (2016b) mapped the distribution of Cretaceous potential source rock pods across the Browse Basin.

Reservoir and Seal Facies

Reservoir facies are best developed within the sand-prone platform GDE (Table 2). Widespread development of this environment occurred in two sequence stratigraphic settings. The first is where this GDE extended to the outboard platform margin (i.e., K10, K40.0, K60.0, and K61.0) (Figure 10). In the central Caswell Sub-basin, the sand-prone platform GDE within the K10 sequence is one of the reservoirs (Brewster Member) in the Ichthys-Prelude and Burnside fields (Figure 2B; Table 2). The second setting is where the sand-prone platform GDE is limited to the inboard basin (i.e., K20, K30, K41.0, and K42.0) (Figure 10) and is typically amalgamated across two or more sequences to form thick reservoir intervals. An example is the reservoir for the Cornea oil and gas field (Figure 2B; Table 2).

The submarine fan GDE is only well documented in the K60.0 and K61.0 sequences, where platform margins delivered sand to the slope and basin-floor. Although hydrocarbon shows are numerous in this stratigraphic interval, only the Caswell oil and Marabou gas accumulations (K60.0) and the Abalone gas accumulation (K61.0) are confidently identified as submarine fan GDE (Figure 2B; Table 2). Parts of the Brewster Member (K10) in the medial Caswell Sub-basin and the Asterias Member (K30) in the northern Caswell Sub-basin were interpreted as submarine fan deposits by Blevin et al. (1998b); seismic imaging of these units is poor, and at least in some locations these sand-rich intervals can alternatively be considered to be sand-prone platform facies. Detailed mapping of 3-D seismic surveys may lead to confirmation of additional occurrences of submarine fan GDEs in the Browse Cretaceous succession.

The Echuca Shoals Formation (K20–K30) or the combined Echuca Shoals and Jamieson (K40) Formations have long been regarded as the regional hydrocarbon seals in the Browse Basin (e.g., Blevin et al., 1998b; Le Poidevin et al., 2015). The present study shows that basin-floor and slope muds are the main seal facies for platform and submarine fan reservoirs. For example, in the central Caswell Sub-basin, K20 muds provide the seal for K10 reservoirs, and K41.0 muds seal K40.0 reservoir facies. Along the inboard basin, basin-floor and slope GDEs progressively back-step and provide the seal for underlying sand-prone platform facies. For example, K30 muds seal K20 platform sands, and K40.0 muds seal K30 platform sands. K42.0 and K50 basin-floor and slope facies, deposited around the time of peak transgression, seal all Lower Cretaceous reservoir facies, except perhaps for parts of the inboard Leveque and Yampi shelves. The K60.0 and K61.0 submarine fan reservoir facies are sealed by intrasequence basin-floor mudstone and marl.

Accumulations, Petroleum Systems, and Plays

Eighteen petroleum accumulations in the Browse Basin include at least one Cretaceous reservoir: 14 in the sand-prone platform GDE and 4 in the submarine fan GDE (Table 2). Figure 19 is a schematic depiction of Browse Cretaceous GDEs, play elements (source, reservoir, and seal), and trap configurations that combine to form hydrocarbon plays. Hydrocarbons from Cretaceous reservoirs have been geochemically linked (Edwards et al., 2016) to the Plover, Vulcan, and Echuca Shoals petroleum systems (Figure 2). The commercial gas accumulations reservoired in the K10 sand-prone platform GDE (e.g., Ichthys-Prelude accumulation) are likely derived from the Vulcan Formation (Jurassic and K10 slope and basin-floor GDEs) marine source-rock interval because the K10 sandstones are encased within a thick marine shale seal that includes the subjacent source rock. Furthermore, the molecular composition indicates that these gases have a higher abundance of the wet gases ethane, propane, butane, and pentane (i.e., average wetness ratio 100 × (C2 + C3 + C4 + C5)/(C1 + C2 + C3 + C4 + C5) = 16.4%) compared with gases found in Jurassic Plover Formation reservoirs at Ichthys-Prelude and neighboring accumulations where the wetness ratio is lower (average wetness ratio = 8.3%) (Rollet et al., 2016a). Contributions to several oil accumulations have been typed to the Echuca Shoals Formation source interval (K20 and K30 basin-floor and slope GDEs; Table 2). Prominent among these is the Cornea oil accumulation, which resides within K41.0–K42.0 amalgamated platform GDEs.

Figure 19.

Schematic representation of Browse Basin Cretaceous sequence stratigraphy, generalized gross depositional environment (GDE), hydrocarbon plays, hydrocarbon accumulations, and petroleum systems.

Figure 19.

Schematic representation of Browse Basin Cretaceous sequence stratigraphy, generalized gross depositional environment (GDE), hydrocarbon plays, hydrocarbon accumulations, and petroleum systems.

The trap element is provided mostly by compaction anticlines (also referred to as “drape” anticlines) over pre-Cretaceous structural highs in the Caswell and Barcoo Sub-basins, often in combination with tilted fault blocks related to Jurassic–earliest Cretaceous extension (Figure 19; Table 2). Other trap configurations include compaction anticlines over Proterozoic paleotopographic basement highs along the inboard basin margin and Miocene inversion anticlines. The large Ichthys-Prelude gas accumulation and other accumulations that include a K10 sand-prone platform reservoir are trapped within a northeast-trending structural corridor in the central Caswell Sub-basin (Figure 2). Compaction folds over paleotopographic basement highs (e.g., Cornea accumulation on the Yampi shelf) are the main trap configuration for hydrocarbons, for which the gas component has migrated from a Plover source and the oil component from an Echuca Shoals source (Longley et al., 2002; Grosjean et al., 2016). There are no known accumulations associated with the stratigraphic pinchout play. A drill test of this play (Pryderi 1), for which the K30 Muderongia australis Sandstone (based on M. australis) was the potential reservoir, was unsuccessful (CalEnergyResources, 2016, unpublished data).

Only three accumulations (all within the K60 sequence) are confidently ascribed to a submarine fan GDE (Table 2). The K50 and K60 source rock quality is poor, so that charge was probably received via faults from an Echuca Shoals source, as indicated at the Caswell oil accumulation. Detailed geochemical analysis using diamondoids and semivolatile aromatic compounds has also suggested a contribution from the Jurassic Plover Formation charging the Caswell oil accumulation through the same fault system (Spaak et al., 2020). Although numerous shows have been recorded, no accumulations are known from the mud-prone platform GDE.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Accommodation History

The Browse Cretaceous succession was deposited during a first-order basin phase of high and then waning thermal subsidence that ensued after the separation of Argo from the outboard Westralian Super Basin. This first-order accommodation is expressed on the inboard basin as an Early Cretaceous transgressive trend, peak transgression during the Turonian, and Late Cretaceous regression.

Second- and third-order sequence architectures were modulated by tectonic movements outside of the Browse Basin related to ongoing Cretaceous breakup of southeastern Gondwana, continent scale epeirogeny, and tectono-eustasy. The architecture of the K10–K30 supersequence resulted from rifting and breakup between the southern Westralian Super Basin and Greater India. This link is established with relatively high confidence by seismic mapping and biostratigraphy.

Tectonic or eustatic controls on deposition of supersequences K40 and K50–K60 are more circumstantial. Second-order flooding at the base of the K40 supersequence corresponds to the Cretaceous peak of marine inundation of the Australian continent. Despite the continent-scale significance of this probable tectonic event, it remains poorly understood. Second-order flooding at the base of the K50–K60 supersequence is attributed to peaks in thermal subsidence rate and tectono-eustasy. Subsequent waning of thermal subsidence and Late Cretaceous epeirogenic uplift resulted in the regression of sand-prone platform sediments into the basin. Second- and third-order accommodation within the Browse Cretaceous succession is linked to tectonic events outside the Browse Basin.

Only the K20 and K20 sequences are confidently linked to plate tectonic events elsewhere in the Westralian Super Basin. Assignment of other Browse Cretaceous sequences to specific plate tectonic events outside of the Westralian Super Basin (e.g., separation of Greater India-Australia and Antarctica-Australia, midocean ridge reorganizations) has been attempted in several studies but must be considered tentative. The main intrabasinal influence on accommodation and sequence architecture in the Browse Basin was enhanced subsidence in depocenters over the Paleozoic rift system, between pre-Cretaceous structural highs.

Hydrocarbon Plays and Systems

Browse Cretaceous sequences include five GDEs (sand-prone platform, mud-prone platform, slope, basin-floor, submarine fan) based on clinoform geometry and are characterized by integration of the lithological description of drill cuttings and wire-line log information from wells. Mapping has yielded the spatial distribution and hierarchical stacking arrangement of GDEs and therefore source, reservoir, and seal play elements at the regional scale. The integrated sequence stratigraphic and GDE framework outlined here provides improved geological context for proven and conceptual hydrocarbon plays in the Browse Cretaceous succession. Moreover, the sequence stratigraphic approach used here predicts the arrangement of play elements in areas of the basin that are untested by drilling and thereby better constrains the distribution of petroleum systems that exist in the Browse Cretaceous succession. We speculate, for example, that the K30–K42.0 reservoirs on the Yampi shelf (e.g., Cornea field) may extend southwest along basin strike. However, we also observe from our GDE maps that these reservoirs may be absent or too distant from Caswell-Barcoo source kitchens to form accumulations over the adjacent Leveque shelf.

REFERENCES CITED

Blevin, J. E., C. J. Boreham, R. E. Summons, H. I. M. Struckmeyer, and T. S. Loutit, 1998a, An effective Lower Cretaceous petroleum system on the North West Shelf; evidence from the Browse Basin, in P. G. Purcell and R. R. Purcell, eds., The sedimentary basins of Western Australia 2: Proceedings of Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium: Perth, Australia, Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, p. 397–420.

Blevin, J. E., H. I. M. Struckmeyer, C. Boreham, D. L. Cathro, J. Sayers, and J. M. Totterdell, 1997, Browse Basin high resolution study. North West Shelf, Australia. Interpretation report: Record 1997/38, 282 p., accessed February 21, 2025, https://pid.geoscience.gov.au/dataset/ga/23689.

Blevin, J. E., H. I. M. Struckmeyer, D. L. Cathro, J. M. Totterdell, C. J. Boreham, K. K. Romine, T. S. Loutit, and J. Sayers, 1998b, Tectonostratigraphic framework and petroleum systems of the Browse Basin, North West Shelf, in P. G. Purcell and R. R. Purcell, eds., The sedimentary basins of Western Australia 2: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium: Perth, Australia, Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, p. 369–395.

Boggs, S., 2001, Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy, 3rd ed.: Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 770 p.

Boreham, C. J., Z. Roksandic, J. M. Hope, R. E. Summons, A. P. Murray, J. E. Blevin, and H. I. M. Struckmeyer, 1997, Browse Basin organic geochemistry study, North West Shelf, Australia. Volume 1: Interpretation report: Record 1997/57, 113 p., accessed February 21, 2025, https://pid.geoscience.gov.au/dataset/ga/24474.

Bradshaw, M. T., A. N. Yeates, R. M. Beynon, A. T. Brakel, R. P. Langford, J. M. Totterdell, and M. Yeung, 1988, Palaeogeographic evolution of the North West Shelf region, in P. G. Purcell and R. R. Purcell, eds., The North West Shelf, Australia: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium: Perth, Australia, Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, p. 29–54.

Catuneanu, O., V. Abreu, J. P. Bhattacharya, M. D. Blum, R. W. Dalrymple, P. G. Eriksson, C. R. Fielding, , 2009, Towards the standardization of sequence stratigraphy: Earth-Science Reviews, v. 92, no. 1–2, p. 1–33, doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2008.10.003.

Direen, N. G., 2012, Comment on “Antarctica — Before and after Gondwana” by S.D. Boger Gondwana Research, Volume 19, Issue 2, March 2011, Pages 335–371: Gondwana Research, v. 21, no. 1, p. 302–304, doi:10.1016/j.gr.2011.08.008.

Edwards, D. S., E. Grosjean, T. Palu, N. Rollet, L. Hall, C. J. Boreham, A. Zumberge, , 2016, Geochemistry of dew point petroleum systems, Browse Basin, Australia: Australian Organic Geochemistry Conference, Fremantle, Australia, December 4–7, 2016, accessed March 10, 2025, https://d28rz98at9flks.cloudfront.net/101720/101720_abstract.pdf.

Embry, A. F., 2010, Correlating siliciclastic successions with sequence stratigraphy, in K. T. Ratcliff and B. A. Zaitlin, eds., Application of modern stratigraphic techniques: Theory and case histories: Tulsa, Oklahoma, SEPM Special Publication 94, p. 35–53.

Embry, A. F., and E. P. Johannessen, 1993, T–R sequence stratigraphy, facies analysis and reservoir distribution in the uppermost Triassic–Lower Jurassic succession, western Sverdrup Basin, Arctic Canada, in T. O. Vorren, E. Bergsager, Ø. A. Dahl-Stamnes, E. Holter, B. Johansen, E. Lie, and T. B. Lund, eds., Arctic geology and petroleum potential. Norwegian Petroleum Society Special Publication 2: New York, Elsevier, p. 121–146.

Emery, D., and K. J. Myers, 1996, Sequence stratigraphy: Oxford, United Kingdom, Blackwell Science, 297 p.

Frakes, L. A., D. Burger, M. Apthorpe, J. Wiseman, M. Dettmann, N. Alley, R. Flint, , 1987, Australian Cretaceous shorelines, stage by stage: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, v. 59, p. 31–48, doi:10.1016/0031-0182(87)90072-1.

Galloway, W. E., 1989, Genetic stratigraphic sequences in basin analysis I: Architecture and genesis of flooding-surface bounded depositional units: AAPG Bulletin, v. 73, p. 125–142, doi:10.1306/703C9AF5-1707-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

Geoscience Australia, 2023, Regional geology of the Browse Basin, accessed February 27, 2025, https://www.ga.gov.au/scientific-topics/energy/province-sedimentary-basin-geology/petroleum/acreagerelease/browse.

Geoscience Australia and Australian Stratigraphy Commission, 2017, Australian stratigraphic units database, accessed February 28, 2025, https://www.ga.gov.au/data-pubs/datastandards/stratigraphic-units.

Gibbons, A. D., U. Barckhausen, P. van den Bogaard, K. Hoernle, R. Werner, J. M. Whittaker, and R. D. Müller, 2012, Constraining the Jurassic extent of Greater India: Tectonic evolution of the West Australian margin: Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, v. 13, no. 5, p. 1–25, doi:10.1029/2011GC003919.

Glorstad-Clark, E., J. I. Faleide, B. A. Lundschien, and J. P. Nystuen, 2010, Triassic seismic sequence stratigraphy and paleogeography of the western Barents Sea area: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 27, no. 7, p. 1448–1475, doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2010.02.008.

Grosjean, E., D. S. Edwards, C. J. Boreham, Z. Hong, J. Chen, and J. Sohn, 2016, Using neo-pentane to probe the source of gases in accumulations of the Browse and Perth Basins: Australian Organic Geochemistry Conference, Fremantle, Australia, December 4–7, 2016, accessed March 10, 2025, https://d28rz98at9flks.cloudfront.net/101680/101680_abstract.pdf.

Grosjean, E., D. S. Edwards, T. J. Kuske, L. Hall, N. Rollet, and J. E. Zumberge, 2015, The source of oil and gas accumulations in the Browse Basin, North West Shelf of Australia: A geochemical assessment: AAPG International Conference and Exhibition, Melbourne, Australia, September 13–16, 2015, 1 p.

Haig, D. W., A. J. Mory, E. McCartain, J. Backhouse, E. Hakansson, A. Ernst, R. S. Nicoll, , 2017, Late Artinskian-early Kungurian (Early Permian) warming and maximum marine flooding in the East Gondwana interior rift, Timor and Western Australia, and comparisons across East Gondwana: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, v. 468, p. 88–121, doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.11.051.

Hall, R., 2012, Late Jurassic-Cenozoic reconstructions of the Indonesian region and the Indian Ocean: Tectonophysics, v. 570–571, p. 1–41, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2012.04.021.

Haq, B. U., 2014, Cretaceous eustasy revisited: Global and Planetary Change, v. 113, p. 44–58, doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.12.007.

Helland-Hansen, W., and O. J. Martinsen, 1996, Shoreline trajectories and sequences: Description of variable depositional-dip scenarios: Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 66, p. 670–688, doi:10.1306/D42683DD-2B26-11D7-8648000102C1865D.

Hocking, R. M., H. T. Moors, and W. J. E. Van de Graaff, 1987, Geology of the Carnarvon Basin Western Australia: Perth, Western Australia, Australia, Geological Survey of Western Australia Bulletin 133, 307 p.

Hubbard, R. J., J. Pape, and D. G. Roberts, 1985, Depositional sequence mapping as a technique to establish tectonic and stratigraphic framework and evaluate hydrocarbon potential on a passive continental margin, in O. R. Berg and D. G. Woolverton, eds., Seismic stratigraphy II: An integrated approach: AAPG Memoir 39, p. 79–91.

Keep, M., and S. J. Moss, 2000, Basement reactivation and control of Neogene structures in the outer Browse Basin, Northwest Shelf: Exploration Geophysics, v. 31, no. 1–2, p. 424–432, doi:10.1071/EG00424.

Kelman, A. P., K. Khider, N. Rollet, S. Abbott, E. Grosjean, and M. Lech, 2017, Browse Basin: Biozonation and stratigraphy, chart 32, accessed February 21, 2025, https://d28rz98at9flks.cloudfront.net/76687/Chart_32_Browse_Basin_2017.pdf.

Kennard, J. M., I. Deighton, D. Ryan, D. S. Edwards, and C. J. Boreham, 2004, Subsidence and thermal history modelling: New insights into hydrocarbon expulsion from multiple systems in the Browse Basin: Timor Sea petroleum geoscience: Proceedings of the Timor Sea Symposium, Darwin, Australia, June 19–20 2003, p. 411–435.

Le Poidevin, S. R., T. J. Kuske, D. S. Edwards, and P. R. Temple, 2015, Browse Basin: Western Australia and Territory of Ashmore and Cartier Islands adjacent area, 2nd ed., Australian petroleum accumulations report 7: Record 2015/10, 115 p., accessed February 21, 2025, https://d28rz98at9flks.cloudfront.net/82545/Rec2015_010.pdf.

Lewis, C. J., and K. N. Sircombe, 2013, Use of U-Pb geochronology to delineate provenance of North West Shelf sediments, Australia, in M. Keep and S. J. Moss, eds., The sedimentary basins of Western Australia 4: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium: Perth, Australia, Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, p. 1–26.

Longley, I. M., C. Buessenschuett, L. Clydsdale, C. J. Cubitt, R. C. Davis, M. K. Johnson, N. M. Marshall, , 2002, The North West Shelf of Australia: A Woodside perspective, in M. Keep and S. J. Moss, eds., The sedimentary basins of Western Australia 3: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium: Perth, Australia, Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, p. 27–88.

Marshall, N. G., and S. C. Lang, 2013, A new sequence stratigraphic framework for the North West Shelf, Australia, in M. Keep and S. J. Moss, eds., The sedimentary basins of Western Australia 4: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium: Perth, Australia, Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, p. 1–32.

Metcalfe, I., 2013, Gondwana dispersion and Asian accretion: Tectonic and palaeogeographic evolution of eastern Tethys: Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, v. 66, p. 1–33, doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.12.020.

Ogg, J. G., G. Ogg, and F. M. Gradstein, 2016, A concise geologic time scale 2016: New York, Elsevier, 240 p.