The AAPG/Datapages Combined Publications Database

AAPG Bulletin

Full Text

![]() Click to view page images in PDF format.

Click to view page images in PDF format.

AAPG Bulletin, V.

DOI: 10.1306/11132524122

Porosity evolution and geometry in Santos Basin Aptian presalt petrofacies

William da Silveira Freitas,1 Thisiane Dos Santos,2 Mariane C. Trombetta,3 Sabrina Danni Altenhofen,4 Argos Belmonte Silveira Schrank,5 Guilherme A. Martinez,6 Anderson J. Maraschin,7 Felipe Dalla Vecchia,8 Amanda Goulart Rodrigues,9 Luiz Fernando De Ros,10 and Rosalia Barili11

1Instituto de Geociências, Campus do Vale, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, Brazil; Institute of Petroleum and Natural Resources (IPR), Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

2IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

3IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

4IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

5Instituto de Geociências, Campus do Vale, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

6IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

7IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

8IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

9Instituto de Geociências, Campus do Vale, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

10Instituto de Geociências, Campus do Vale, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

11Instituto de Geociências, Campus do Vale, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; IPR-PUCRS, Porto Alegre, Brazil; [email protected]

ABSTRACT

The presalt deposits from offshore southeastern Brazil account for approximately 3/4 of the total hydrocarbon production of the country. Consequently, they are the subject of various studies aimed at better understanding the primary and diagenetic controls on their reservoir quality. The Barra Velha Formation (Aptian, Santos Basin) constitutes the main reservoirs of the presalt sag section, essentially composed of magnesian clays, calcite spherulites and fascicular shrubs, and intraclasts reworked from these aggregates. The pore systems of these rocks are highly complex, owing to depositional and diagenetic controls. Therefore, the origin and distribution of porosity and permeability are difficult to understand. To better understand and characterize the pore systems of the unusual presalt reservoirs, this study aimed to recognize the relationships among their porosity and permeability values and pore types within the context of the evolution and geometry of their pore systems. X-ray microtomography scanning of 251 samples from 3 wells was performed to obtain the three-dimensional ( 3-D

3-D ) porosity distribution, and the main pore types were described in detail in 583 thin sections. Thirteen petrofacies were defined for the studied samples, and the

) porosity distribution, and the main pore types were described in detail in 583 thin sections. Thirteen petrofacies were defined for the studied samples, and the  3-D

3-D pore network was reconstructed for characteristic samples of each petrofacies. Image segmentation was applied to quantify pore sizes and shapes, as well as to visualize the connections between them. Petrofacies with low quality or considered nonreservoirs correspond to rocks in which the magnesian clay matrix was partially replaced by dolomite or for which dolomite or silica filled interparticle pores where pores were generated by matrix dissolution, leading to poorly connected vuggy pores. High-quality reservoirs, however, correspond to in situ rocks with porosity generation occurring mainly through widespread dissolution of the Mg-clay matrix, further enhanced by the dissolution of calcite spherulites and shrubs. They also correspond to reworked rocks with high interparticle primary porosity and crystalline rocks formed by pervasive dolomite replacement followed by dissolution, creating intercrystalline porosity. Dissolution played a significant role in increasing not only porosity but also pore connectivity and pore size, as observed through pore network segmentation tools and through the Area

pore network was reconstructed for characteristic samples of each petrofacies. Image segmentation was applied to quantify pore sizes and shapes, as well as to visualize the connections between them. Petrofacies with low quality or considered nonreservoirs correspond to rocks in which the magnesian clay matrix was partially replaced by dolomite or for which dolomite or silica filled interparticle pores where pores were generated by matrix dissolution, leading to poorly connected vuggy pores. High-quality reservoirs, however, correspond to in situ rocks with porosity generation occurring mainly through widespread dissolution of the Mg-clay matrix, further enhanced by the dissolution of calcite spherulites and shrubs. They also correspond to reworked rocks with high interparticle primary porosity and crystalline rocks formed by pervasive dolomite replacement followed by dissolution, creating intercrystalline porosity. Dissolution played a significant role in increasing not only porosity but also pore connectivity and pore size, as observed through pore network segmentation tools and through the Area  3-D

3-D , EqDiameter, and ShapeVA3D attributes. Increased understanding of the presalt reservoir porosity patterns is important not only for exploring for new accumulations but also for optimizing the recovery from currently producing reservoirs.

, EqDiameter, and ShapeVA3D attributes. Increased understanding of the presalt reservoir porosity patterns is important not only for exploring for new accumulations but also for optimizing the recovery from currently producing reservoirs.

INTRODUCTION

Most of the presalt hydrocarbon reserves in Brazil are contained in the Barra Velha Formation (BVF), corresponding to the Santos Basin Aptian sag section (Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis, 2025). These rocks represent a unique combination of calcite aggregates, magnesian phyllosilicates, dolomite, and silica (Schrank et al., 2024). The controls of primary and diagenetic characteristics on the quality of these reservoirs are still poorly understood.

The petrographic characterization of the main sag reservoirs revealed that they are composed of divergent fibrous aggregates with a fascicular-optical fabric, characteristic of abiotic chemical precipitation of carbonates in various environments, such as some travertines (Pentecost, 1990; Chafetz and Guidry, 1999; Fouke et al., 2000; Aguillar et al., 2024), Precambrian stromatolites (Grotzinger and Knoll, 1999; Riding, 2008), and lakes (Jones and Renaut, 1994; Warren, 2006; Della Porta, 2015). Another interesting aspect of the presalt system corresponds to the voluminous and recurrent deposition of magnesian silicates, such as stevensite and kerolite (Carramal et al., 2022; Silva et al., 2022; Schrank et al., 2024). These clays were commonly replaced and locally encrusted by spherulitic and fascicular calcite aggregates, as well as replaced by dolomite and silica or dissolved, giving rise to spherulitic reservoirs with secondary porosity (Herlinger et al., 2017; Wright and Barnett, 2017, 2020; Lima and De Ros, 2019). Some characteristics of the Aptian presalt deposits can be essentially understood as a product of recurrent, high-frequency, and alternating precipitation of calcite and magnesian silicates. Another very common feature of the presalt is the occurrence of intense dissolution, dolomitization, and silicification in the vicinity of major faults and other structures, which can be characterized as hydrothermal alterations (Vieira de Luca et al., 2017; Lima et al., 2020; Wennberg et al., 2021; Strugale et al., 2024).

One of the main challenges in evaluating carbonate reservoirs is understanding the relationship between pore type, porosity, and permeability (Lønøy, 2006). Carbonate rocks commonly contain a variety of pore types that can vary in size over several orders of magnitude (Weger et al., 2009). The pore systems of carbonate rocks are complex, and reservoirs typically contain various pore types of both primary and secondary origin (Mazzullo and Chilingarian, 1992; Worden et al., 2018); however, understanding the pore systems of the presalt reservoirs represents additional challenges because the knowledge of the primary processes and controls on porosity is still incomplete, as is the understanding of the impact of diagenesis on reservoir quality. Existing classifications of carbonate pore types and pore systems can be partially adapted to the presalt reservoirs, but the genetic, geometric, and petrophysical aspects of the presalt porosity and the influence of diagenesis on the pore systems are poorly understood.

Digital rock technology is another approach for studying the petrophysical properties of complex reservoirs, such as those with fractures, complex wettability, or high clay content (Wang et al., 2022). There is a growing body of work that is attempting to apply digital rock or machine learning methods to the presalt carbonates and possible analogues (Rezende et al., 2013; Hosa et al., 2020; Basso et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Berriguete et al., 2022; Matheus et al., 2023)—in most cases ignoring the complex and unusual characteristics of the presalt rocks. Consequently, most of these proposals have generated models that are quite unrealistic in relation to the geologic and petrologic aspects of the presalt reservoirs.

The main objective of this study was to characterize the geometry of the pore systems of the BVF presalt reservoirs and the controls exerted on them by the primary and diagenetic aspects during their evolution. To do this, we employed a combination of quantitative petrography, high-resolution three-dimensional ( 3-D

3-D ) images obtained through x-ray microtomography, and conventional petrophysical analysis (porosity and permeability) in selected petrofacies to understand the main controls impacting reservoir quality. Understanding the genesis, evolution, and geometry of porosity in these reservoirs will contribute to optimizing their production efficiency in the Santos Basin and in exploration for similar reservoirs.

) images obtained through x-ray microtomography, and conventional petrophysical analysis (porosity and permeability) in selected petrofacies to understand the main controls impacting reservoir quality. Understanding the genesis, evolution, and geometry of porosity in these reservoirs will contribute to optimizing their production efficiency in the Santos Basin and in exploration for similar reservoirs.

GEOLOGIC SETTING

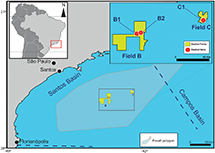

Santos Basin (Figure 1), located in the southeastern Brazilian continental margin, is the widest of the peri-Atlantic basins, bordered to the north by the Campos Basin through the Cabo Frio high and to the south by the Pelotas Basin through the Florianópolis high. It is the largest offshore basin in the country, covering approximately 350,000 km2 (Moreira et al., 2007). The basin was formed through the breakup of the Gondwana supercontinent and the creation of the South Atlantic Ocean during the Early Cretaceous (Lentini et al., 2010; Blaich et al., 2011; Chaboureau et al., 2013; Freitas et al., 2019; Baptista et al., 2023). The crystalline basement of the Santos Basin is constituted by Precambrian granites and gneisses of the Coastal Complex and meta-sediments of the Ribeira Belt (Moreira et al., 2007; Mohriak et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Location map of the Santos Basin, showing the presalt polygon, with an area of 149,000 km2, the studied fields (in yellow), and the wells (in red).

Figure 1.

Location map of the Santos Basin, showing the presalt polygon, with an area of 149,000 km2, the studied fields (in yellow), and the wells (in red).

The initial exploration of the basin occurred in the 1970s. Pereira and Feijó (1994) developed the first chronostratigraphic model for the depositional sequences of the basin. The study conducted by (Moreira et al., 2007) refined that previous model, with better distinction of the depositional sequences. Mohriak (2003) interpreted different extensional phases in the evolution of the basin. The onset of extension was associated with asthenospheric uplift and lithospheric thinning. Subsequent phases encompassed lithospheric stretching during rifting, characterized by the extrusion of basaltic lavas and establishment of rift hemigraben systems filled with lacustrine sediments during the Neocomian-Barremian. At the end of rifting, an episode of lithospheric stretching and uplifting enabled the reactivation of faults and the formation of a vast regional unconformity, the Pre-Alagoas unconformity (Kumar and Gamboa, 1979).

This tectonic evolution resulted in the formation of relatively small lakes during the rift phase, followed by regional uplift, erosion, and thermal subsidence, promoting the creation of a very large lake during the sag phase. The basin was then filled with Aptian lacustrine sediments (Mohriak, 2003). The Florianópolis high blocked the inflow of marine waters from the south. After marine waters could finally enter the large depression, thick and extensive salt layers covered the lacustrine sediments at the end of the Aptian (Farias et al., 2019).

Moreira et al. (2007) divided the basin fill into three depositional supersequences: rift, sag, and drift. The first is composed of the Guaratiba Group, which includes the Camboriú, Piçarras, and Itapema Formations. The Camboriú Formation consists of tholeiitic basalts, representing the economic basement of the basin (Moreira et al., 2007; Mohriak et al., 2012). The Piçarras Formation comprises alluvial fan polymictic conglomerates and sandstones composed of basalt, quartz, and feldspar fragments in proximal parts and sandstones, siltstones, and mudstones rich in magnesian clays in the lacustrine parts (Moreira et al., 2007). The Itapema Formation consists of proximal alluvial sandstones and conglomerates, bivalve bioclast calcirudites and calcarenites (“coquinas”), and distal carbonates intercalated with organic dark mudstones that are the main source rocks of the basin (Moreira et al., 2007).

The contact with the sag supersequence is defined by the Pre-Alagoas regional unconformity (Figure 2; Moreira et al., 2007). Deposition of the BVF occurred in an alkaline lacustrine environment with high rates of evaporation, promoting the formation of calcite spherulites within a matrix of magnesium silicates and crusts composed of fascicular calcite shrubs. Initially, these deposits were interpreted as microbial (Terra et al., 2010). However, they were reinterpreted as products of abiotic precipitation in an alkaline system (Wright and Barnett, 2015, 2020; Carramal et al., 2022; Wright, 2022; Schrank et al., 2024). The Ariri Formation corresponds to Aptian evaporites, products of repeated marine incursions and desiccations, in an arid climate (Moreira et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Lower Cretaceous stratigraphic chart for the Santos Basin (modified from Moreira et al., 2007; Wright and Barnett, 2015).

Figure 2.

Lower Cretaceous stratigraphic chart for the Santos Basin (modified from Moreira et al., 2007; Wright and Barnett, 2015).

The Drift supersequence encompasses the Camburi, Frade, and Itamambuca Groups (Moreira et al., 2007; Wright and Barnett, 2015). The Camburi Group comprises siliciclastic alluvial fan deposits, shallow platform carbonates, and distal shales deposited during the Albian, as well as proximal alluvial fan deposits, distal shales, and marls associated with turbidites (Moreira et al., 2007). The Frade Group consists of alluvial fan deposits from the Santos Formation, fluvial sandstones from the Juréia Formation, and shales and mudstones from the Itajaí-Açu Formation (Moreira et al., 2007). The Itamambuca Group comprises fluvial sandstones from the Ponta Aguda Formation, calcarenites and calcirudites from the Iguapé Formation, and the Marambaia Formation, composed of shales, mudstones, marls, and diamictites (Moreira et al., 2007).

DEPOSITIONAL ENVIRONMENT

The in situ rocks of the BVF were deposited in an extensive meromictic lacustrine system, characterized by a water column stratified into oxygenated (mixolimnion) and anoxic (monimolimnion) layers, separated by a chemocline (De Ros, 2018). This stratification controls mineral precipitation and favors calcite formation in the upper levels and magnesium clays with spherulites in the lower levels. Rapid variations in the depth of the chemocline influenced the observed lithologic changes (Carvalho et al., 2022). This depositional model explains the abrupt alternation between porous and nonporous facies without requiring frequent lake-level fluctuations. The lack of subaerial exposure markers and the isotopic homogeneity between basins support the interpretation of a chemically and structurally stable lacustrine system, which is key for understanding and exploring presalt reservoirs.

The reworked deposits of the BVF are composed of intraclasts derived from in situ spherulitic and fascicular deposits, recemented by fascicular calcite, and interbedded on a millimeter-to-centimeter scale (Carvalho and Fernandes, 2021; Altenhofen et al., 2024). Their wide distribution, good grain-size sorting, and rounded morphology indicate that they do not follow a purely gravitational model (Saller et al., 2016; Camargo et al., 2022). The absence of traction structures suggests that internal waves, triggered by disturbances in the chemocline of stratified lakes, were responsible for reworking processes, promoting episodic erosion and redistribution (Rodríguez-Berriguete et al., 2022; Altenhofen et al., 2024). Multiple reworking cycles, associated with ooids having intraclasts as nuclei, indicate frequent hydrodynamic disturbances in a stable lacustrine system, controlled by internal oscillations of the water column (Gomes et al., 2020; Carramal et al., 2022; Wright, 2022).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The methodology of this work followed the workflow shown in Figure 3, comprising different analyses that were integrated for interpreting the pore systems of the characteristic BVF petrofacies and their controls. The entire study was based on analyses conducted on three wells located in the Santos Basin. The production data from the wells in field B are confidential. In contrast, well C1 belongs to one of the most prolific presalt fields in Brazil, reaching a production level of 47,347 bbl/day of oil and 1.374 Mm3/d of natural gas (Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis, 2025).

Figure 3.

Analytical workflow performed on the studied samples. μCT = microtomography;

Figure 3.

Analytical workflow performed on the studied samples. μCT = microtomography;  3-D

3-D = three-dimensional.

= three-dimensional.

Core Description

A total of 48.4 m of cores were described from well B1 and 70.6 m from well C1 at a 1:20 scale. Facies were classified according to De Ros and Oliveira (2023). Well B2 cores were not available for description.

The lithostratigraphic logs were elaborated in digital format using Adobe Illustrator software. Core analyses and descriptions were integrated with porosity and permeability data to visualize the distribution of facies and petrophysical data. Facies analysis allowed understanding of the heterogeneities of the studied wells and the formation of the studied sag phase presalt deposits of the Santos Basin.

Petrography

A total of 583 thin sections (266 from well B1, 120 from well B2, and 197 from well C1) from the selected wells was described using Petroledge software (De Ros et al., 2007), a system to assist in the acquisition, processing, and sharing of generated petrographic data. Petrographic quantification was performed by counting 300 points per thin section and through visual estimation and comparative tables. All thin sections were prepared from samples impregnated with blue epoxy resin to highlight the porosity. Staining with a solution of alizarin and potassium ferrocyanide allowed identification of the carbonate species (Dickinson, 1966).

The descriptions were performed on ZEISS AXIO A1M and Leica DM750P transmitted light microscopes, with crossed and uncrossed polarizers. Photomicrographic documentation was obtained using ZEN 3.1 Blue Edition and LAS × 5.0.2 software, using AxioCam ICc 3 Flexacam C1 and C3 cameras attached to the microscopes. The system of De Ros and Oliveira (2023) was used for the classification of petrofacies of the in situ and redeposited rocks.

X-Ray Microtomography

Computerized microtomography analysis was conducted in three stages: (1) image acquisition; (2) reconstruction of microtomography sections, aimed at processing the images and making  corrections

corrections to construct the

to construct the  3-D

3-D volume; and (3) calculation of the total or partial volume of the scanned samples. The microtomography images were captured using SkyScan 1173 equipment, which uses a microfocus x-ray source operating at 130 kV and 61 μA. Pixel sizes ranged from 7 to 35.7 μm and were analyzed using brass filters of 0.25 mm to mitigate beam-hardening effects. The acquisition process involved a 270° or 360° rotation of the object, with a fixed rotation step of 0.2°. At each angular position, a transmission image was captured and stored as 16-bit TIFF files on the hard disk. Following acquisition, reconstruction was performed using a

volume; and (3) calculation of the total or partial volume of the scanned samples. The microtomography images were captured using SkyScan 1173 equipment, which uses a microfocus x-ray source operating at 130 kV and 61 μA. Pixel sizes ranged from 7 to 35.7 μm and were analyzed using brass filters of 0.25 mm to mitigate beam-hardening effects. The acquisition process involved a 270° or 360° rotation of the object, with a fixed rotation step of 0.2°. At each angular position, a transmission image was captured and stored as 16-bit TIFF files on the hard disk. Following acquisition, reconstruction was performed using a  3-D

3-D cone beam algorithm, which accounted for the thickness of the object. Once reconstruction was complete, a

cone beam algorithm, which accounted for the thickness of the object. Once reconstruction was complete, a  3-D

3-D image was generated. AVIZO Thermo Scientific software was used for segmentation, individualization of pores, pore size, and pore shape analyses.

image was generated. AVIZO Thermo Scientific software was used for segmentation, individualization of pores, pore size, and pore shape analyses.

Petrophysics

Conventional petrophysical data from three wells were evaluated in this study. Part of the porosity and permeability data were obtained from the Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis, and another part was analyzed using the AP-608 Porosimeter-Permeameter at the Petroleum and Natural Resources Institute of Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul. The tested samples were plugs of 1 and 1.5 in. in diameter and 1 in. in length. In total, the petrophysical porosity and permeability from 149 samples from well B1, 88 samples from well B2, and 64 samples from well C1 were evaluated and integrated with other results to assess the key factors controlling the reservoir quality of the rocks.

RESULTS

Cores Description

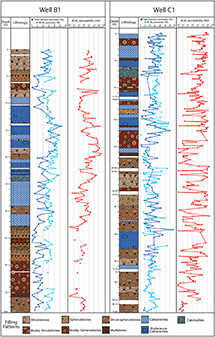

Lithologic description of the cores allowed the identification of six in situ facies (Figure 4) and three redeposited facies (Figure 5). The two cores exhibit distinct characteristics and demonstrate significant heterogeneity (Figure 6). Core B1 is characterized by a dominance of in situ rocks at its base and top, with reworked deposits predominating in the intermediate part. There is limited silicification at the top of the core. The in situ interval at the base is 16.13 m thick and contains high-frequency intercalations of various in situ facies. The reworked deposits have a maximum thickness of 8.7 m, mainly comprising calcarenites and rudaceous calcarenites, with thicknesses reaching up to 4.53 and 3.2 m, respectively.

Figure 4.

Summary of the main in situ classes of the analyzed samples according to the classification of De Ros and Oliveira (2023).

Figure 4.

Summary of the main in situ classes of the analyzed samples according to the classification of De Ros and Oliveira (2023).

Figure 5.

Summary of the main reworked classes of the analyzed samples according to the classification of De Ros and Oliveira (2023).

Figure 5.

Summary of the main reworked classes of the analyzed samples according to the classification of De Ros and Oliveira (2023).

Figure 6.

Summary of the description of the cores with the distribution of porosity and permeability throughout them. RCAL = routine core analysis.

Figure 6.

Summary of the description of the cores with the distribution of porosity and permeability throughout them. RCAL = routine core analysis.

Core C1 exhibits a dominance of reworked deposits, with significant in situ deposits intercalated at the top. In the intermediate part, there is a predominance of in situ rocks, with limited reworked deposits among them. At the base of the core, in situ rocks occur, with subordinate reworked deposits. The in situ rocks form a 17.45-m-thick package, predominantly composed of shrub-spherulstones and shrubstones. The reworked deposits are up to 2.18 m thick, represented mostly by calcarenites and rudaceous calcarenites.

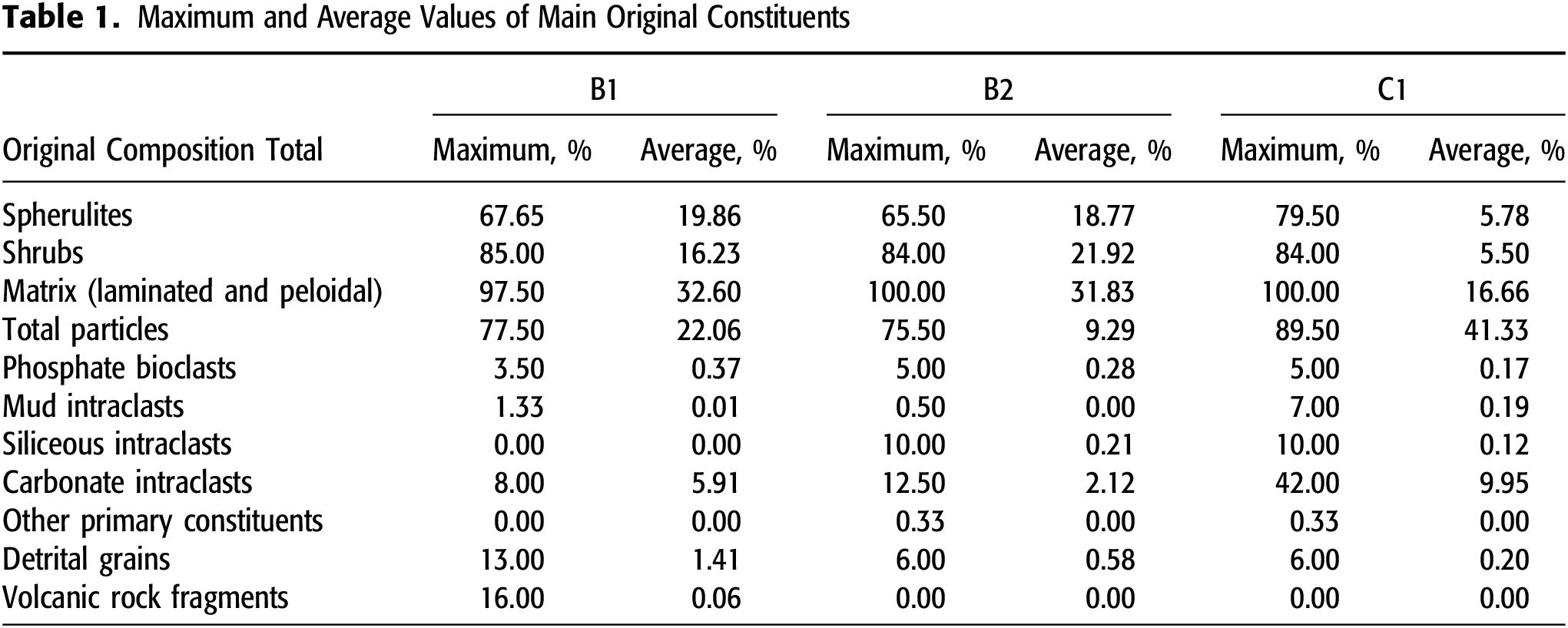

Primary Composition and Texture

The in situ rocks exhibit a diversity of textures and structures (Table 1). Muddy spherulstones often display irregular lamination due to the distribution, concentration, and coalescence of spherulites (Figure 7A). Shrub-spherulstones exhibit irregular lamination due to the alternation of levels with predominance of spherulites or shrubs (Figure 7B). Mudstones show both planar-parallel and irregular lamination (Figure 7C). Reworked samples generally appear with a massive structure (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Main primary components observed in the studied wells. (A) Muddy spherulstone with irregular distribution of Mg-clay matrix and calcite spherulites; crossed polarizers (XP). (B) Shrubstone formed by large fascicular aggregates with preferential vertical growth (XP). (C) Mudstone with plane-parallel lamination; uncrossed polarizers (//P). (D) Massive calcarenite with interparticle porosity (blue) (//P).

Figure 7.

Main primary components observed in the studied wells. (A) Muddy spherulstone with irregular distribution of Mg-clay matrix and calcite spherulites; crossed polarizers (XP). (B) Shrubstone formed by large fascicular aggregates with preferential vertical growth (XP). (C) Mudstone with plane-parallel lamination; uncrossed polarizers (//P). (D) Massive calcarenite with interparticle porosity (blue) (//P).

In the well B1 core, the in situ samples display laminations characterized by the distribution of spherulites, shrubs, and clay peloids within the Mg-silicate matrix. Calcite spherulites and shrubs replaced the original Mg-silicate matrix and usually engulfing peloids (Schrank et al., 2024). The spherulites have a radius of 0.2 to 0.6 mm, whereas the shrubs are generally larger than 1 mm. The matrix of magnesian phyllosilicates (Carramal et al., 2022; Schrank et al., 2024) is common in this core and is usually partially or completely replaced by blocky and saddle dolomite, microcrystalline quartz cryptocrystalline silica, and microcrystalline calcite, or it is simply dissolved. Silt and fine-sand siliciclastic grains of feldspars, quartz, micas, rutile, tourmaline, and zircon occur locally mixed in the matrix.

In the well B2 core, the phyllosilicate matrix of the in situ samples was generally replaced by blocky dolomite, microcrystalline quartz, cryptocrystalline silica, and microcrystalline calcite. Calcite is the most common component in the analyzed samples, found mainly as spherulitic and fascicular aggregates of millimeter to centimeter size. These aggregates are often recrystallized into micro- to macrocrystalline anhedral mosaics or as triangular sectors following the original crystal orientation.

In the well C1 core, in situ rocks are less common than in the other two wells. Calcite is the most important component in these samples; it occurs in the form of spherulitic, fascicular, and microcrystalline carbonate intraclasts, carbonate intraclasts, shrub and spherulite, and clay ooid generated over a carbonate intraclast. Blocky dolomite, cryptocrystalline, fibrous-radiated chalcedony, and coarsely crystalline quartz occur replacing matrix, followed by framework-replacive and filling interstitial space.

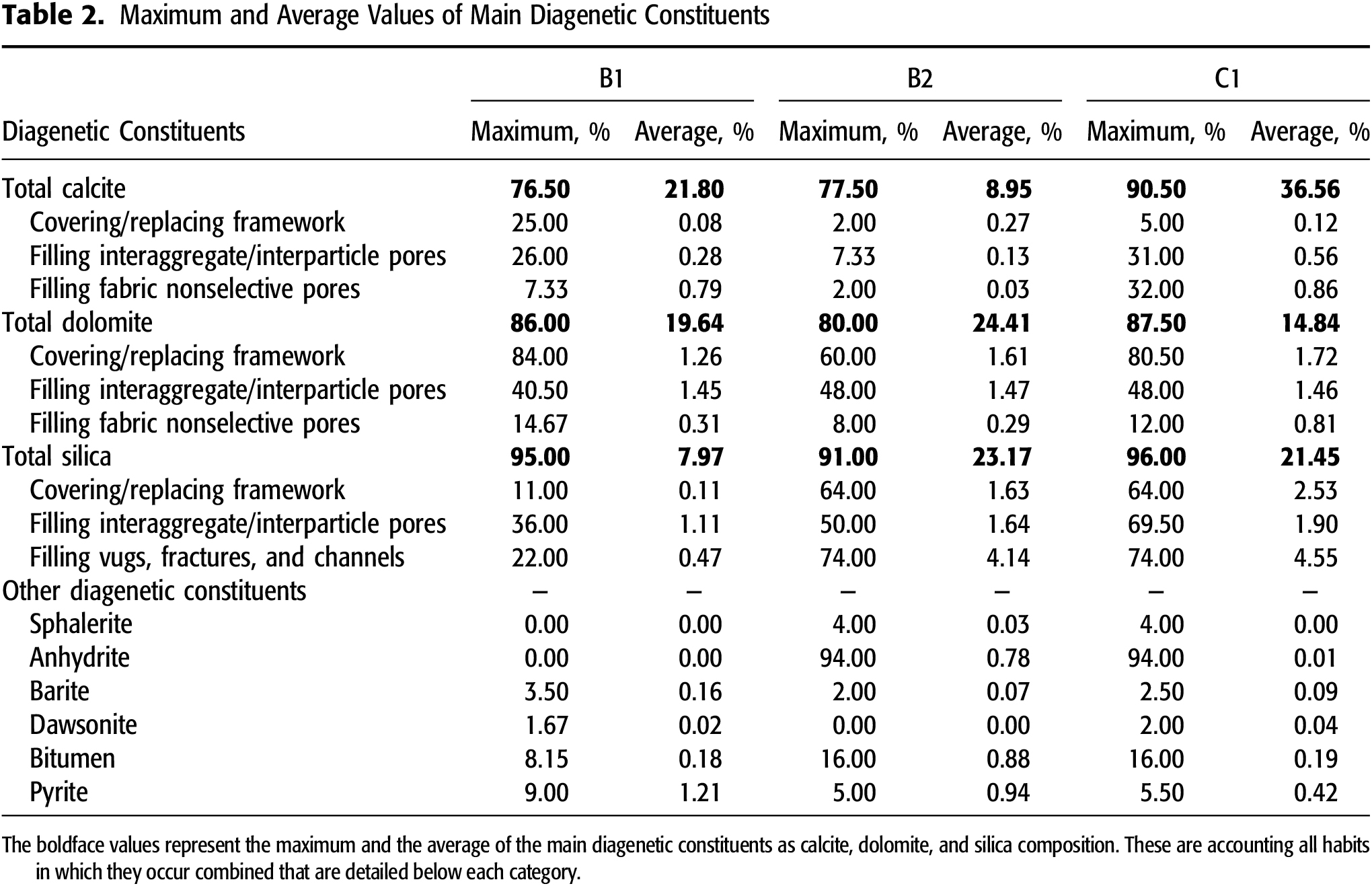

Diagenetic Processes and Products

The main diagenetic constituents in the analyzed samples are calcite, dolomite, and silica. Other diagenetic phases in smaller quantities include sphalerite, anhydrite, barite, dawsonite, bitumen, and pyrite (Table 2).

The main diagenetic processes that impacted the petrophysical properties of the studied rocks were dissolution, cementation, replacement, and compaction (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Main diagenetic components observed in the studied wells. (A) Detail of blocky calcite covering fascicular calcite (yellow arrow) in shrubstone (uncrossed polarizers, //P). (B) Blocky calcite rim calcite covering intraclast (//P). (C) Blocky dolomite filling interparticle porosity among calcite intraclasts (stained) (//P). (D) Detail of matrix being replaced by blocky dolomite (//P). (E) Shrubstone constituted by large coalesced fascicular aggregates with interaggregate porosity filled by chalcedony (crossed polarizers, XP). (F) Microcrystalline quartz replacing calcite spherulites (yellow arrow) (XP).

Figure 8.

Main diagenetic components observed in the studied wells. (A) Detail of blocky calcite covering fascicular calcite (yellow arrow) in shrubstone (uncrossed polarizers, //P). (B) Blocky calcite rim calcite covering intraclast (//P). (C) Blocky dolomite filling interparticle porosity among calcite intraclasts (stained) (//P). (D) Detail of matrix being replaced by blocky dolomite (//P). (E) Shrubstone constituted by large coalesced fascicular aggregates with interaggregate porosity filled by chalcedony (crossed polarizers, XP). (F) Microcrystalline quartz replacing calcite spherulites (yellow arrow) (XP).

Dissolution

Dissolution played a significant role as the primary process of porosity generation in these rocks. Matrix dissolution porosity is generally abundant, although in many cases it is perceptible only from replacive dolomite crystals that appear to float within the pores formed by dissolution. Pores among the calcite aggregates were also generated in part by the dissolution of Mg-clay peloids. The shrinkage and partial or complete dissolution of the syngenetic Mg-silicate matrix correspond to the main origin of the porosity present in the analyzed rocks. Matrix dissolution also significantly contributed to permeability, especially where the generated pores were not filled with dolomite, silica, or calcite cement.

In addition, the partial or complete dissolution of shrubs, spherulites, intraclastic particles, and secondary constituents resulted in intra-aggregate and intraparticle porosity, contributing considerably to total porosity values. However, this process did not contribute to increasing permeability because these pores are poorly connected.

Cementation and Replacement

Besides forming the characteristic spherulites and shrubs, diagenetic calcite occurs in the form of blocky crystals that replaced the matrix, partially filling the pores formed by its dissolution in the in situ rocks and interparticle pores in redeposited rocks, as well as vugular pores. Blocky crystals also locally rim the aggregates and intraclasts. Both blocky and macrocrystalline calcite filled pores in the in situ and reworked samples. Microcrystalline calcite replaced clay peloids, intraclasts, and matrix, and also the rare microbial deposits. However, macrocrystalline calcite commonly filled pores from dissolution of matrix, intraclasts, and peloids, as well as fracture, vugular, and interparticle pores.

Dolomite is found in both in situ and reworked rocks, most commonly as euhedral rhombs, often replacing the matrix, calcite aggregates, or particles, but it also acted as cement, filling or rimming the pores. Microcrystalline dolomite also replaced the matrix, calcite aggregates, or particles, and rimmed the carbonate particles. In addition, dolomite formed lamellar aggregates, filling matrix contraction pores and replacing the syngenetic matrix. In some areas, dolomite pseudomorphically replaced the spherulites and shrubs. Saddle dolomite replaced the matrix, aggregates, peloids, and intraclasts, with characteristic wavy extinction and defective shapes. It also filled intra-aggregate and intraparticle dissolution pores, as well as channel and vug pores. Macrocrystalline dolomite is found mostly as cement, filling fractures and channels and replacing the matrix.

Microcrystalline quartz commonly replaced components such as carbonate aggregates, intraclasts, Mg-silicate matrix, peloids, and ostracod bioclasts, whereas macrocrystalline quartz partially filled pores, especially fractures and dissolution pores in calcite aggregates. Both micro- and macrocrystalline quartz filled interparticle, interaggregate, vugular, channel, and fracture pores, also replacing intraclasts, spherulites, and Mg-silicate matrix. Prismatic quartz is generally found as isolated crystals in inter- and intra-aggregate pores. Fibro-radiated chalcedony is frequently observed in strongly silicified rocks replacing the matrix and spherulites and also filling matrix dissolution and vugular pores. Microcrystalline quartz and cryptocrystalline silica often replaced carbonate intraclasts and aggregates, as well as peloids and Mg-clay matrix in strongly altered samples. Prismatic quartz filled fracture pores in aggregates and intraclasts, channel, vugular, interparticle, and interaggregate pores, as well as pores from the dissolution of aggregates and intraclasts. Drusiform quartz typically filled large vugular matrix dissolution and fractures, while prismatic quartz rimmed intra-aggregate, vugular, channel, and fracture pores.

Porosity

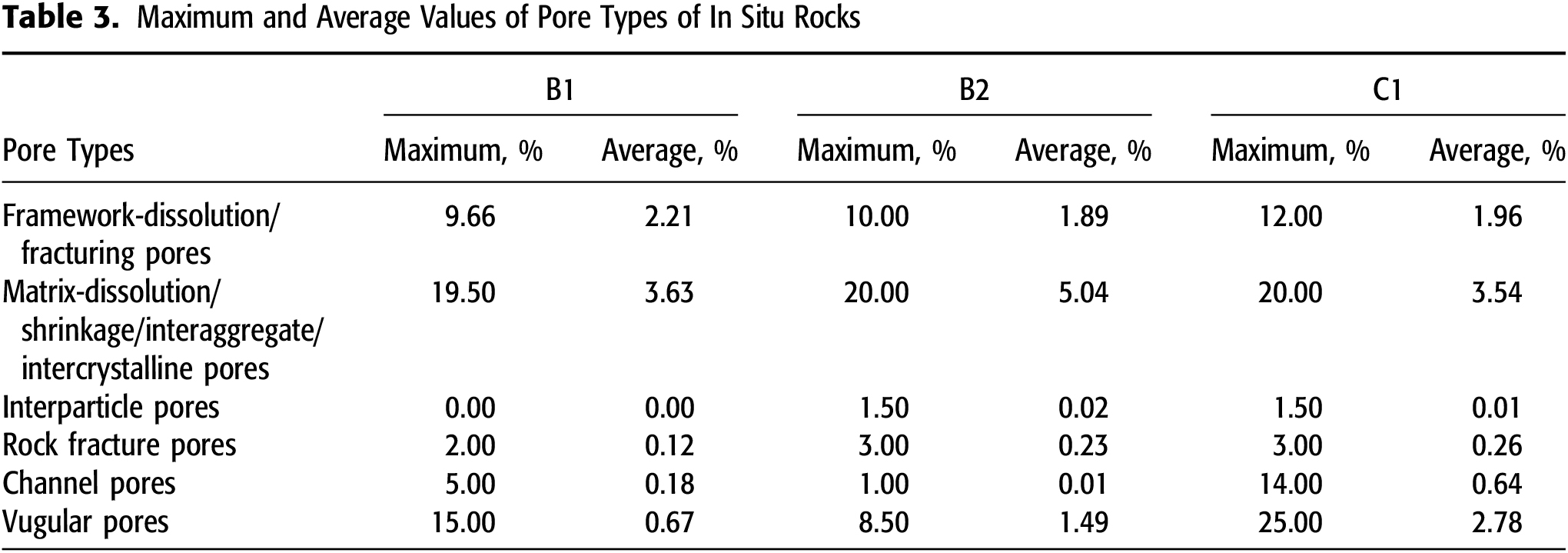

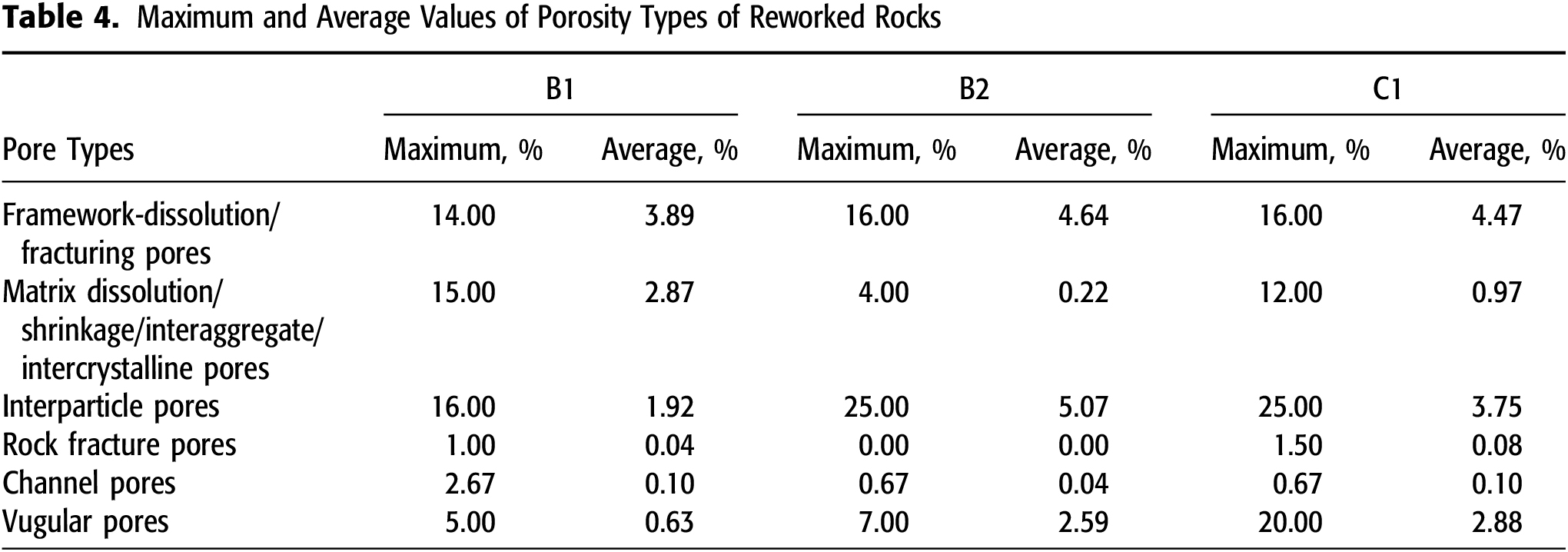

The pore types were classified according to the Choquette and Pray (1970) system, with some adaptation for the studied sag phase rocks of the BVF (Figure 9). The results are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Figure 9.

Main types of pores identified in the studied rocks. (A) Interaggregate (yellow arrow) and vugular porosity with remnants of peloidal matrix (red arrow) in shrubstone (uncrossed polarizers, //P). (B) Pores from shrinkage of the laminated clay matrix, partially replaced by blocky dolomite (//P). (C) Vugular porosity, partially reduced by dolomite cementation (//P). (D) Interparticle, intraparticle (red arrow), and vugular porosity (yellow arrow) in intraclastic rock (//P). (E) Detail of intraparticle porosity due to intraclast dissolution in intraclastic calcarenite cemented by silica (//P). (F) Detail of intercrystalline (red arrow) and intracrystalline (yellow arrow) porosity in dolomite (//P).

Figure 9.

Main types of pores identified in the studied rocks. (A) Interaggregate (yellow arrow) and vugular porosity with remnants of peloidal matrix (red arrow) in shrubstone (uncrossed polarizers, //P). (B) Pores from shrinkage of the laminated clay matrix, partially replaced by blocky dolomite (//P). (C) Vugular porosity, partially reduced by dolomite cementation (//P). (D) Interparticle, intraparticle (red arrow), and vugular porosity (yellow arrow) in intraclastic rock (//P). (E) Detail of intraparticle porosity due to intraclast dissolution in intraclastic calcarenite cemented by silica (//P). (F) Detail of intercrystalline (red arrow) and intracrystalline (yellow arrow) porosity in dolomite (//P).

Porosity of the In Situ Deposits

In the in situ samples from wells B1, B2, and C1, interaggregate pores are the most prevalent types, which can correspond either to primary porosity in some shrubstones or to a secondary result of matrix dissolution. The occurrence of intra-aggregate dissolution pores, formed either cutting through or following the internal crystalline fabric, is also common. Intra-aggregate dissolution pores were also formed due to the dissolution of engulfed peloids. Despite being quite common, intra-aggregate pores do not contribute to effective porosity and permeability because they are poorly connected. Vugular pores are quite common and often are found completely cemented in substantially altered rocks. Where these pores are not obstructed, they play a crucial role in increasing sample permeability. Fractures and channel pores are less frequent, but where volumetrically significant contribute to high permeabilities, akin to the vugular pores.

Porosity of the Redeposited Deposits

The most common type of porosity in the reworked samples corresponds to intraparticle pores resulting from the dissolution of intraclasts, followed by interparticle pores, interpreted as essentially primary depositional but also subordinately from the dissolution of the clay matrix or dolomite cement. Particle fracture pores may significantly increase local permeability. Intracrystalline and intercrystalline pores are particularly important in some strongly silicified and dolomitized rocks. Other locally significant pore types in these lithotypes include fractures, channel, and vugular pores, where not partially or completely cemented.

Permeability

Petrophysical porosity and permeability values were plotted for the three studied wells (Figure 10). In the three wells, permeability shows a wide range, from very low permeability to very high values, which is due to the depositional and diagenetic heterogeneity characteristic of the presalt reservoirs.

Figure 10.

Log crossplots of porosity × permeability showing the values for the lithologic classes in the three studied wells.

Figure 10.

Log crossplots of porosity × permeability showing the values for the lithologic classes in the three studied wells.

There are significant differences in permeability among the three studied cores. In well B1, the best permeabilities are found in the in situ rocks. Shrubstones show values of up to 1923 md in this well, and it is the class with the best permeability values relative to the porosity. Shrub-spherulstones also show good permeability values, reaching up to 962 md. Among the reworked rocks of well B1, the class with the best permeability are the rudaceous calcarenites, with up to 861.32 md.

The same is observed in the well B2 core, where the in situ rocks represent the best permeability values, along with some of the redeposited rocks. The best classes in terms of permeability are shrubstones, shrub-spherulstones, and rudaceous calcarenites, with maximum values of 1530, 2980, and 812 md, respectively.

In well C1, there is a predominance of reworked rocks, and thus the best permeability values are found among them. Arenaceous calcirudites, slightly rudaceous calcarenites, and rudaceous calcarenites are the classes with the best permeability values, with maximum values of 1166.7, 716.08, and 954.83 md, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Reservoir Petrofacies

The present study applied the reservoir petrofacies concept (sensu De Ros and Goldberg, 2007) as an approach to assess the influence of diagenetic, depositional textural, and compositional factors on the reservoir quality of the BVF rocks.

Reservoir petrofacies are characterized by the complex interaction among predominant depositional structures, textures and primary composition, and diagenetic processes controlling porosity. In this study, 13 representative reservoir petrofacies were defined for the BVF samples.

The initial petrofacies definition involved their classification (sensu De Ros and Oliveira, 2023). Specific parameters were then applied to each class. Each petrofacies is identified by a mnemonic code that is related to the classification and the main porosity modifier. For example, IntracSil refers to petrofacies formed by intraclastic rocks with high silica content filling interparticle and nonfabric selective pores. For the in situ rocks, nine petrofacies are defined: MudShrPor, MudShrDolPor, MudSpheDol, MudSphePor, MudSpheMtx, Mudstone, ShrPor, ShrSil, and ShrDolPor. The defining criteria encompass the following attributes: (1) textural: the framework volume, namely, the calcite aggregates volume and degree of coalescence, and the volume of the original matrix; (2) connected porosity: volume of interstitial and nonfabric-selective porosity; and (3) diagenetic constituents: types and volume of main diagenetic constituents affecting porosity, including both matrix replacement and filling matrix dissolution pores.

For reworked rocks, three petrofacies were defined: IntracDol, IntracSil, and IntracPor. To define petrofacies in intraclastic rocks, the following criteria were used: (1) total volume of connected porosity, corresponding to the sum of interparticle porosity and nonfabric-selective porosity (vugs, channels, and fracture pores); and (2) main diagenetic constituent controlling porosity connection, which can be cementation by dolomite, silica, or calcite. In addition to in situ and reworked rocks, one more reservoir petrofacies was defined for pervasively dolomitized crystalline rocks (DolostonePor).

The 13 defined petrofacies were grouped into 4 distinct petrofacies associations, classified as nonreservoir poor, fair, good, and very good (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Microtomographic images of examples of reservoir petrofacies applied to in situ and redeposited presalt reservoirs. After coding the petrofacies, they are grouped into associations directly related to reservoir quality (nonreservoir poor, fair, good, and very good).

Figure 11.

Microtomographic images of examples of reservoir petrofacies applied to in situ and redeposited presalt reservoirs. After coding the petrofacies, they are grouped into associations directly related to reservoir quality (nonreservoir poor, fair, good, and very good).

Geometry and Distribution of Porosity in the Petrofacies

The pore space in presalt spherulitic reservoirs derives from the diagenetic dissolution of the original matrix composed by magnesian clays within which the calcite spherulites grew (Tosca and Wright, 2015; Wright and Barnett, 2015; Carramal et al., 2022). In contrast, in the shrubstones, porosity was developed both as primary, growth-framework pores among the calcite shrubs (Herlinger et al., 2023) and by the extensive dissolution of the intershrub matrix (Schrank et al., 2024). Porosity of the intraclastic rocks is more conventional, similar to typical carbonate and siliciclastic rocks (Herlinger et al., 2017, 2023), and is controlled by both depositional and diagenetic factors, as shown by Altenhofen et al. (2024). Particle size remains a fundamental control of their pore system, where coarser-grained particles tend to have larger pores, throats, and permeability, whereas better sorting results in higher original porosity (Herlinger et al., 2023).

The quality of presalt reservoirs was also significantly influenced by dolomitization and silicification promoted by diagenetic or hydrothermal processes (Lima and De Ros, 2019), which have commonly decreased porosity and permeability due to the reduction of pore throats. Different forms of silicification and dolomitization of the presalt carbonates of the Campos and Santos Basin in Brazil and the Kwanza Basin in Angola have been linked to early and late burial diagenetic processes and to hydrothermal processes (Saller et al., 2016; Teboul et al., 2017; Vieira de Luca et al., 2017; Lima and De Ros, 2019; Lima et al., 2020; Basso et al., 2023; Strugale et al., 2024).

The use of x-ray microtomography allowed the visualization and quantification of rock components and a realistic description of the geometry of the pore systems in  3-D

3-D (De Boever et al., 2012; Matheus et al., 2023) and integration of these data with the reservoir petrofacies defined through systematic petrography. In this section, the pore systems of each petrofacies are presented, with their most representative pore types and connection patterns, which directly affect their permeability.

(De Boever et al., 2012; Matheus et al., 2023) and integration of these data with the reservoir petrofacies defined through systematic petrography. In this section, the pore systems of each petrofacies are presented, with their most representative pore types and connection patterns, which directly affect their permeability.

Very Good Reservoir Quality

High permeability values are associated with petrofacies ShrPor due to large pore throats connecting mostly primary growth-framework pores formed among the fascicular calcite aggregates during their precipitation as crusts on the sediment-water interface (Herlinger et al., 2017; Hosa et al., 2020). The pore network is heterogeneous and complex, controlled by the essentially vertical growth of the fascicular aggregates, and the distribution of pores and throats is controlled by the coalescence and relative location of the shrubs, as described by Herlinger et al. (2023). The most important pore types are the interaggregate and vuggy pores, which significantly contribute to increased porosity and permeability. Figure 12A shows a microtomographic image from the pore system of a representative sample of this petrofacies. The connection among pores is shown in Figure 12B, where macropores interconnect, forming large fluid conduits. The pores with the highest number of connections are highlighted in red. The MudShrPor rocks exhibit more than 15% interstitial, nonfabric selective porosity, mainly from intershrub matrix dissolution, reaching 33%. High permeability results from well-connected pores controlled by large throats (Herlinger et al., 2017; Hosa et al., 2020). Secondary interaggregate and vuggy pores dominate. The MudSphePor shows >15% macroporosity from matrix dissolution, forming smaller pores than shrubstones (Herlinger et al., 2023). Main porosity is secondary interaggregate pores, with rare vuggy and intra-aggregate pores. The IntracPor, reworked rocks with >15% macroporosity, rank among the best reservoirs alongside ShrPor. The pore system is complex, well connected, and controlled by particle size, featuring interparticle, intraparticle, vuggy, and fracture pores that boost permeability.

Figure 12.

Pore systems of the petrofacies segmented through high-resolution x-ray microtomography of petrofacies. (A) Pore system of a ShrPor, (B) corresponding pore connections, and (C) equivalent thin section. (D) Pore system of a MudShrDolPor, (E) corresponding pore connections, and (F) equivalent thin section. (G) Pore system of an IntracDol petrofacies, (H) corresponding pore connections, and (I) equivalent thin section. (J) Segmented pore system of a ShrSil petrofacies, (K) corresponding pore connections, and (L) equivalent thin section. (M) Segmented pore system of an IntracSil petrofacies, (N) corresponding pore connections, and (O) equivalent thin section.

Figure 12.

Pore systems of the petrofacies segmented through high-resolution x-ray microtomography of petrofacies. (A) Pore system of a ShrPor, (B) corresponding pore connections, and (C) equivalent thin section. (D) Pore system of a MudShrDolPor, (E) corresponding pore connections, and (F) equivalent thin section. (G) Pore system of an IntracDol petrofacies, (H) corresponding pore connections, and (I) equivalent thin section. (J) Segmented pore system of a ShrSil petrofacies, (K) corresponding pore connections, and (L) equivalent thin section. (M) Segmented pore system of an IntracSil petrofacies, (N) corresponding pore connections, and (O) equivalent thin section.

Good Reservoir Quality

In MudShrDolPor petrofacies samples, dolomite is a main diagenetic constituent, both directly replacing the original matrix and cementing the matrix dissolution porosity. The volume of interstitial and nonfabric selective porosity reaches 13%. The most common pores are interaggregate and intercrystalline, resulting from matrix dissolution, with few vugular pores. The average pore size is smaller than in MudShrPor (Table 3), due to the dolomite crystals. Although there is a good range of porosity, permeability values are lower because dolomite reduced the connection among the pores, as shown in Figure 12D, where it is possible to see more spaced pores and with fewer connections (Figure 12E). The DolostonePor has >50% dolomite replacement, erasing original textures but maintaining relatively high macroporosity. High permeability stems from well-connected intercrystalline pores (Tamoto et al., 2024). Some large pores may be fracturing artifacts. Intracrystalline porosity, important here, was undetectable by microtomography.

Fair Reservoir Quality

The IntracDol samples have low petrographic macroporosity (<10%) due to abundant dolomite content in the interstitial spaces, both filling interparticle porosity and replacing clay matrix and peloids. Where porosity reduction is dominated by dolomite cementation, a strong impact on throat size relative to pore size is observed, as described by Herlinger et al. (2023). A microtomographic image of the resulting complex pore system is shown in Figure 12G, with scattered pores and few connections among them (Figure 12H). Some cases show good permeability values, despite the interparticle presence of dolomite. This occurs where dolomite cementation creates a network of intercrystalline pores, partially enlarged by slight dolomite dissolution (De Boever et al., 2012). The MudShrDol has heterogeneous pore systems: dolomite creates flow barriers and reduces average pore size, even in shrub-dominated facies.

Poor and Nonreservoir Quality

The ShrSil petrofacies refers to shrubstones with a large volume of interaggregate silica and low porosity and permeability. Silica in the interaggregate space also occurs, filling interaggregate and nonfabric selective porosity and replacing minor clay matrix. The extensive silica cementation reduced the originally high porosity and permeability related to the shrubstone texture (Basso et al., 2023). Such silica-cemented rocks may constitute flow barriers. This is supported by some cases of silicified samples, whose petrophysical porosity ranges from 8% to 12%, but permeabilities are <1 md. The pore system presented in Figure 12J shows a region with some clustered pores, whereas most of the sample lacks any porosity. Figure 12K shows that the areas with macropores are poorly connected due to the presence of silica.

In MudSpheDol, dolomite is also the main diagenetic constituent, either directly replacing the original matrix or cementing the matrix dissolution porosity. These samples exhibit only up to 5% of interstitial and nonfabric selective macroporosity. The abundant formation of dolomite in the interspherulite spaces was favored by the release of Mg2+ from the meta-stable magnesian clays (Fournier et al., 2018; Schrank et al., 2024), creating pore systems with very low porosity and permeability. The pores are restricted to intra-aggregate pores and poorly connected vugs, which do not effectively contribute to permeability.

The MudSpheMtx features >15% preserved matrix, with small, unconnected pores and very low permeability. Mudstone samples have <8% macroporosity, with magnesian clay matrix preserved or replaced by microcrystalline calcite, dolomite, or silica. Rare pores are small, yielding very low permeability, mainly from laminated matrix dissolution; IntracSil has <10% porosity filled by interstitial silica, often cementing moldic and intraparticle pores. Despite relatively high macroporosity, permeability is low due to poor pore connectivity (Figure 12M, N).

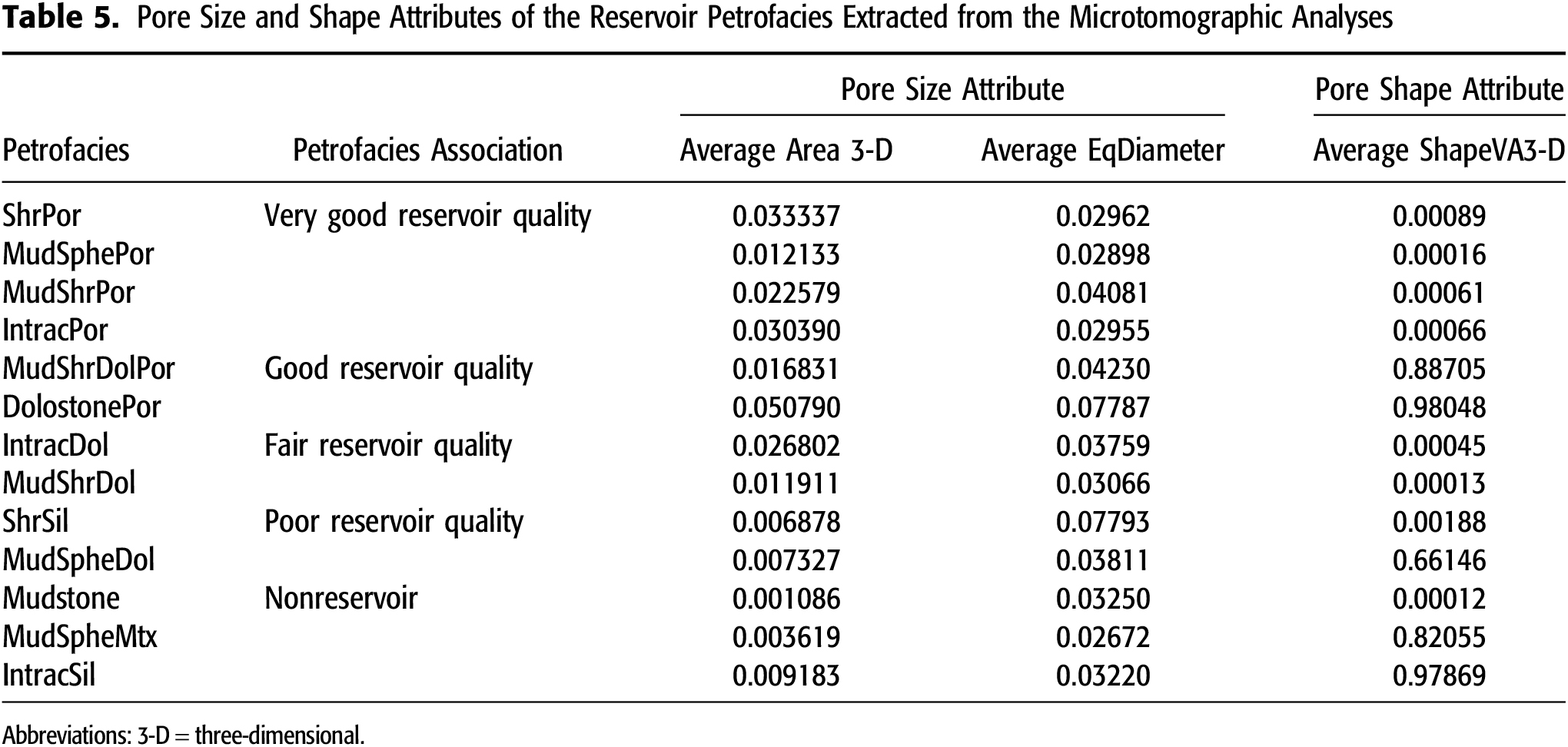

Size and Shapes of the Pores from the Petrofacies

The extraction of morphological pore attributes followed the same methodology used by Herlinger and Vidal (2022). Two attributes related to pore size were analyzed: Area  3-D

3-D , which is the pore boundary area responsible for the exposed surface of the external voxels, and EqDiameter, which represents the diameter of a sphere with the same volume (Herlinger and Vidal, 2022). In addition, one attribute related to pore shape, ShapeVA3D, defined as sphericity (the closer to 1, the more equant the pores are), was calculated using AVIZO software. The analysis revealed significant differences between the petrofacies, which are closely related to reservoir quality. As expected, the attributes related to pore size showed that the petrofacies associated with very good reservoir quality have larger pores (Figure 13; Table 5).

, which is the pore boundary area responsible for the exposed surface of the external voxels, and EqDiameter, which represents the diameter of a sphere with the same volume (Herlinger and Vidal, 2022). In addition, one attribute related to pore shape, ShapeVA3D, defined as sphericity (the closer to 1, the more equant the pores are), was calculated using AVIZO software. The analysis revealed significant differences between the petrofacies, which are closely related to reservoir quality. As expected, the attributes related to pore size showed that the petrofacies associated with very good reservoir quality have larger pores (Figure 13; Table 5).

Figure 13.

Distribution of the average area three-dimensional pore size in the defined petrofacies.

Figure 13.

Distribution of the average area three-dimensional pore size in the defined petrofacies.

The ShrPor (porous shrubstone) petrofacies show the highest permeability values, largely due to the  3-D

3-D intercalation of the calcite fascicular shrubs, forming larger and less equant pores, with wider throats than the other petrofacies (Figure 14A). The interparticle pores of the IntracPor petrofacies are more equant and could be schematically represented as tetrahedral or rhombohedral, connected by more or less lamellar throats, similar to the shapes of typical intergranular pores of siliciclastic rocks (Figure 14B). In contrast, pores generated by matrix dissolution tend to be smaller and frequently below the resolution of the x-ray microtomography equipment. The larger pores generated by dissolution of the laminated Mg-clay matrix are commonly lamellar (Figure 14C), although laterally discontinuous. The pore systems of petrofacies where dolomitization is a major diagenetic process are also characterized by smaller pore sizes. The presence of dolomite rhombs scattered (“floating”) within the pores, typically generated by partial replacement of the matrix followed by its dissolution, created pore systems with smaller pore size and lower pore-to-throat size ratio, which is expected to decrease the residual oil saturation of those petrofacies (Herlinger et al., 2023). Pore-lining dolomite cement reduced the interaggregate porosity, however, in the in situ rocks and the interparticle pores in the intraclastic rocks.

intercalation of the calcite fascicular shrubs, forming larger and less equant pores, with wider throats than the other petrofacies (Figure 14A). The interparticle pores of the IntracPor petrofacies are more equant and could be schematically represented as tetrahedral or rhombohedral, connected by more or less lamellar throats, similar to the shapes of typical intergranular pores of siliciclastic rocks (Figure 14B). In contrast, pores generated by matrix dissolution tend to be smaller and frequently below the resolution of the x-ray microtomography equipment. The larger pores generated by dissolution of the laminated Mg-clay matrix are commonly lamellar (Figure 14C), although laterally discontinuous. The pore systems of petrofacies where dolomitization is a major diagenetic process are also characterized by smaller pore sizes. The presence of dolomite rhombs scattered (“floating”) within the pores, typically generated by partial replacement of the matrix followed by its dissolution, created pore systems with smaller pore size and lower pore-to-throat size ratio, which is expected to decrease the residual oil saturation of those petrofacies (Herlinger et al., 2023). Pore-lining dolomite cement reduced the interaggregate porosity, however, in the in situ rocks and the interparticle pores in the intraclastic rocks.

Figure 14.

Schematic representation of the main pore systems of the studied rocks. (A) Pore scheme of shrubstones, represented by tetrahedral pores. (B) Schematic of pores in intraclast rocks, represented by tetrahedra connected by lamellae. (C) Schematic pores of muddy shrubstones, represented by lamellae, interrupted by the presence of spherulites.

Figure 14.

Schematic representation of the main pore systems of the studied rocks. (A) Pore scheme of shrubstones, represented by tetrahedral pores. (B) Schematic of pores in intraclast rocks, represented by tetrahedra connected by lamellae. (C) Schematic pores of muddy shrubstones, represented by lamellae, interrupted by the presence of spherulites.

The pore shape attributes are also closely linked to the petrofacies. The highest average ShapeVA3D values are found in petrofacies with the presence of dolomite (the closer to 1, the more equant the pores are). This is a characteristic attribute of the intercrystalline pores among the dolomite rhombs. Another petrofacies with a high value is mudstone. In this petrofacies, the higher value may be related to the microtomographic scan resolution. Here, most pores are smaller than the resolution, and the few detected pores appear as points that are considered spherical in the calculation. The IntracSil petrofacies also show high ShapeVA3D values due to the pore-lining cementation of a large part of the interparticle pores by silica, leaving only the center of the originally larger pores uncemented.

CONCLUSIONS

The integration of petrographic and petrophysical data into the geologic reservoir model requires a careful upscaling process that transforms microscopic and laboratory observations into representative model-scale properties. Detailed modeling of pore systems is essential for optimizing hydrocarbon exploration and production in the Santos Basin presalt because it enables the identification of key controls on reservoir quality, prediction of the spatial distribution of porosity and permeability, and reduction of uncertainties in the characterization of producing zones. This enhanced understanding directly contributes to better exploratory target selection, completion strategy planning, and more efficient field development. The analysis of Aptian presalt samples from three wells of two fields from the Santos Basin allowed various observations and inferences regarding the pore system, pore types, and porosity geometry in the different established petrofacies, as in the following.

• Petrographic and x-ray microtomography analyses revealed the high complexity of the pore systems of the presalt BVF in the Santos Basin. The interaction of depositional and diagenetic processes resulted in interaggregate, intra-aggregate, interparticle, intraparticle, intercrystalline, vuggy, fracture, and channel pores.

• The integrated application of microtomographic, petrophysical, and petrographic analysis allowed enhanced characterization of reservoir quality and porosity geometry.

• Systematic petrographic characterization defined 13 petrofacies and 5 petrofacies associations (nonreservoir, poor, fair, good, and very good).

• Petrofacies with high reservoir quality are characterized by large and well-connected pores and high porosity, whereas petrofacies with low quality have reduced porosity and smaller pores with low connectivity, mainly due to the presence of preserved matrix, dolomite, and silica.

• The segmentation of porosity through x-ray microtomography allowed the visualization of the  3-D

3-D pore systems and the quantification of pore sizes and their connections. Microtomography showed excellent correlation with the classification of petrofacies and the petrofacies associations defined by petrography.

pore systems and the quantification of pore sizes and their connections. Microtomography showed excellent correlation with the classification of petrofacies and the petrofacies associations defined by petrography.

• Dolomitization and silicification had a significant impact on the permeability of the petrofacies. Petrofacies with abundant dolomite show lower permeability values due to reduced pore throat sizes. Petrofacies with silica exhibit low permeability values and small pores.

• A detailed understanding of pore systems and accurate characterization of petrofacies are essential for optimizing hydrocarbon exploration and production in the Santos Basin presalt because they are critical for upscaling and feeding reservoir models to make them more realistic.

• Despite the advances, significant challenges remain in characterizing the Santos Basin presalt reservoirs. The application of digital rock technologies integrated with detailed petrography can improve the understanding of depositional and diagenetic controls on reservoir quality, considering the complexity of the presalt carbonate pore systems.

• The characterization of the evolution and the main controls on the porosity of both the in situ and reworked presalt rocks are essential for understanding their complex pore systems. Such knowledge shall contribute to optimizing the hydrocarbon exploration and production of the main Santos Basin reservoirs, and of other equivalent reservoirs in other South Atlantic basins.

REFERENCES CITED

Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis, 2025, Boletim da produção de petróleo e gás natural, Maio 2025/no. 177, 30 p., accessed August 2, 2025, https://www.gov.br/anp/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins-anp/boletins/arquivos-bmppgn/2025/maio.pdf.

Aguillar, J., J. T. F. Oste, M. M. Erthal, P. F. Dal’ Bó, Á. Rodríguez-Berriguete, M. Mendes, and H. Claes, 2024, Depositional and diagenetic processes in travertines: A comprehensive examination of Tocomar basin lithotypes, northwest Argentina: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, v. 142, 104960, 22 p., doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2024.104960.

Altenhofen, S. D., A. G. Rodrigues, L. Borghi, and L. F. De Ros, 2024, Dynamic re-sedimentation of lacustrine carbonates in the Buzios Field, pre-salt section of Santos Basin, Brazil: Journal of South American Earth Sciences, v. 138, 104863, 23 p., doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2024.104863.

Baptista, R. J., A. E. Ferraz, C. Sombra, E. V. Santos Neto, R. Plawiak, C. L. L. Silva, A. L. Ferrari, N. Kumar, and L. A. P. Gamboa, 2023, The presalt Santos Basin, a super basin of the twenty-first century: AAPG Bulletin, v. 107, no. 8, p. 1369–1389, doi:10.1306/04042322048.

Basso, M., G. F. Chinelatto, A. M. P. Belila, L. C. Mendes, J. P. P. Souza, D. Stefanelli, A. C. Vidal, and J. F. Bueno, 2023, Characterization of silicification and dissolution zones by integrating borehole image logs and core samples: A case study of a well from the Brazilian pre-salt: Petroleum Geoscience, v. 29, no. 3, 21 p., doi:10.1144/petgeo2022-044.

Basso, M., J. P. P. Souza, B. C. Z. Honório, L. H. Melani, G. F. Chinelatto, A. M. P. Belila, and A. C. Vidal, 2022, Acoustic image log facies and well log petrophysical evaluation of the Barra Velha Formation carbonate reservoir from the Santos Basin, offshore Brazil: Carbonates and Evaporites, v. 37, no. 3, 50, 23 p., doi:10.1007/s13146-022-00791-4.

Blaich, O. A., J. I. Faleide, and F. Tsikalas, 2011, Crustal breakup and continent-ocean transition at South Atlantic conjugate margins: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 116, no. B1, 38 p., doi:10.1029/2010JB007686.

Camargo, M. M., G. F. Chinelatto, M. Basso, and A. C. Vidal, 2022, Electrofacies definition and zonation of the Lower Cretaceous Barra Velha Formation carbonate reservoir in the pre-salt sequence of the Santos Basin, SE Brazil: Journal of Petroleum Geology, v. 45, no. 4, p. 439–459, doi:10.1111/jpg.12827.

Carramal, N. G., D. M. Oliveira, A. S. M. Cacela, M. A. A. Cuglieri, N. P. Rocha, S. M. Viana, S. L. V. Toledo, S. Pedrinha, and L. F. De Ros, 2022, Paleoenvironmental insights from the deposition and diagenesis of Aptian Pre-Salt magnesium silicates from the Lula Field, Santos Basin, Brazil: Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 92, no. 1, p. 12–31, doi:10.2110/jsr.2020.139.

Carvalho, A. M. A., Y. Hamon, O. G. Souza Jr., N. G. Carramal, and N. Collard, 2022, Facies and diagenesis distribution in an Aptian pre-salt carbonate reservoir of the Santos Basin, offshore Brazil: A comprehensive quantitative approach: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 141, 105708, 25 p., doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105708.

Carvalho, M. D., and F. L. Fernandes, 2021, Pre-salt depositional system: Sedimentology, diagenesis, and reservoir quality of the Barra Velha Formation, as a result of the Santos Basin tectono-stratigraphic development, in M. R. Mello, P. O. Yilmaz, and B. J. Katz, eds., The supergiant Lower Cretaceous pre-salt petroleum systems of the Santos Basin, Brazil: AAPG Memoir 124, p. 121–154.

Chaboureau, A. C., F. Guillocheau, C. Robin, S. Rohais, M. Moulin, and D. Aslanian, 2013, Paleogeographic evolution of the central segment of the South Atlantic during Early Cretaceous times: Paleotopographic and geodynamic implications: Tectonophysics, v. 604, p. 191–223, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2012.08.025.

Chafetz, H. S., and S. A. Guidry, 1999, Bacterial shrubs, crystal shrubs, and ray-crystal shrubs: Bacterial vs. abiotic precipitation: Sedimentary Geology, v. 126, no. 1–4, p. 57–74, doi:10.1016/S0037-0738(99)00032-9.

Choquette, P. W., and L. C. Pray, 1970, Geologic nomenclature and classification of porosity in sedimentary carbonates: AAPG Bulletin, v. 54, no. 2, p. 207–250, doi:10.1306/5d25c98b-16c1-11d7-8645000102c1865d.

De Boever, E., C. Varloteaux, F. H. Nader, A. Foubert, S. B. Békri, S. Youssef, and E. Rosenberg, 2012, Quantification and prediction of the 3D pore network evolution in carbonate reservoir rocks: Oil & Gas Science and Technology – Revue d’IFP Energies Nouvelles, v. 67, no. 1, p. 161–178, doi:10.2516/ogst/2011170.

De Ros, L. F., 2018, Genesis and evolution of Aptian pre-salt carbonate reservoirs in southeastern Brazilian margin (abs.): Brazilian Petroleum Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, June 19–21, 2018, 1 p., doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.12290.09922.

De Ros, L. F., and K. Goldberg, 2007, Reservoir petrofacies: A tool for quality characterization and prediction: AAPG Search and Discovery article 50055, accessed October 15, 2022, https://www.searchanddiscovery.com/documents/2007/07117deros/images/deros.pdf.

De Ros, L. F., K. Goldberg, M. Abel, F. Victoreti, M. Mastella, and E. Castro, 2007, Advanced acquisition and management of petrographic information from reservoir rocks using the Petroledge system: AAPG Annual Convention and Exhibition, Long Beach, California, April 1–4, 2007, accessed December 11, 2025, https://www.searchanddiscovery.com/abstracts/html/2007/annual/abstracts/goldberg2.htm.

De Ros, L. F., and D. M. Oliveira, 2023, An operational classification system for the South Atlantic pre-salt rocks: Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 93, no. 10, p. 693–704, doi:10.2110/jsr.2022.103.

Della Porta, G., 2015, Carbonate build-ups in lacustrine, hydrothermal and fluvial settings: Comparing depositional geometry, fabric types and geochemical signature, in D. W. J. Bosence, K. A. Gibbons, D. P. Le Heron, W. A. Morgan, T. Pritchard, and B. A. Vining, eds., Microbial carbonates in space and time: Implications for global exploration and production: Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2015, v. 418, p. 17–68.

Dickinson, J. A. D., 1966, Carbonate identification and genesis as revealed by staining: Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, v. 36, p. 491–505, doi:10.1306/74D714F6-2B21-11D7-8648000102C1865D.

Farias, F., P. Szatmari, A. Bahniuk, and A. B. França, 2019, Evaporitic carbonates in the pre-salt of Santos Basin—Genesis and tectonic implications: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 105, p. 251–272, doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.04.020.

Fouke, B. W., J. D. Farmer, D. J. Des Marais, L. Pratt, N. C. Sturchio, P. C. Burns, and M. K. Discipulo, 2000, Depositional facies and aqueous-solid geochemistry of travertine-depositing hot springs (Angel Terrace, Mammoth Hot Springs, Yellowstone National Park, USA): Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 70, no. 3, p. 565–585, doi:10.1306/2DC40929-0E47-11D7-8643000102C1865D.

Fournier, F., M. Pellerin, Q. Villeneuve, T. Teillet, F. Hong, E. Poli, J. Borgomano, P. Léonide, and A. Hairabian, 2018, The equivalent pore aspect ratio as a tool for pore type prediction in carbonate reservoirs: AAPG Bulletin, v. 102, no. 7, p. 1343–1377, doi:10.1306/10181717058.

Freitas, V. A., R. M. Travassos, and M. B. Cardoso, 2019, Bacia de Santos, Sumário geológico e setores em oferta, Brasilia DF, Brazil, Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis, 16a Rodada de Solicitações, 19 p., accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.gov.br/anp/pt-br/rodadas-anp/rodadas-concluidas/concessao-de-blocos-exploratorios/14a-rodada-licitacoes-blocos/arquivos/areas-oferta/sumario-santos.pdf.

Gomes, J. P., R. B. Bunevich, L. R. Tedeschi, M. E. Tucker, and F. F. Whitaker, 2020, Facies classification and patterns of lacustrine carbonate deposition of the Barra Velha Formation, Santos Basin, Brazilian pre-salt: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 113, 104176, 21 p., doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104176.

Grotzinger, J. P., and A. H. Knoll, 1999, Stromatolites in Precambrian carbonates: Evolutionary mileposts or environmental dipsticks?: Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, v. 27, no. 1, p. 313–358, doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.27.1.313.

Herlinger, R. Jr., L. F. De Ros, R. Surmas, and A. C. Vidal, 2023, Residual oil saturation investigation in Barra Velha Formation reservoirs from the Santos Basin, offshore Brazil: A sedimentological approach: Sedimentary Geology, v. 448, 106372, 15 p., doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2023.106372.

Herlinger, R. Jr., and A. C. Vidal, 2022, X-ray μCt extracted pore attributes to predict and understand Sor using ensemble learning techniques in the Barra Velha pre-salt carbonates, Santos Basin, offshore Brazil: Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, v. 212, 110282, 16 p., doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110282.

Herlinger, R. Jr., E. E. Zambonato, and L. F. De Ros, 2017, Influence of diagenesis on the quality of lower Cretaceous pre-salt lacustrine carbonate reservoirs from northern Campos Basin, offshore Brazil: Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 87, no. 12, p. 1285–1313, doi:10.2110/jsr.2017.70.

Hosa, A., R. A. Wood, P. W. M. Corbett, R. S. de Souza, and E. Roemers, 2020, Modelling the impact of depositional and diagenetic processes on reservoir properties of the crystal-shrub limestones in the ‘pre-salt’ Barra Velha Formation, Santos Basin, Brazil: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 112, 104100, 10 p., doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104100.

Jones, B., and R. W. Renaut, 1994, Crystal fabrics and microbiota in large pisoliths from Laguna Pastos Grandes, Bolivia: Sedimentology, v. 41, no. 6, p. 1171–1202, doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.1994.tb01448.x.

Kumar, N., and L. A. P. Gamboa, 1979, Evolution of the São Paulo Plateau (southeastern Brazilian margin) and implications for the early history of the South Atlantic: GSA Bulletin, v. 90, no. 3, p. 281–293, doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1979)90<281:EOTSPP>2.0.CO;2.

Lentini, M. R., S. I. Fraser, H. S. Sumner, and R. J. Davies, 2010, Geodynamics of the central South Atlantic conjugate margins: Implications for hydrocarbon potential: Petroleum Geoscience, v. 16, no. 3, p. 217–229, doi:10.1144/1354-079309-909.

Lima, B. E. M., and L. F. De Ros, 2019, Deposition, diagenetic and hydrothermal processes in the Aptian pre-salt lacustrine carbonate reservoirs of the northern Campos Basin, offshore Brazil: Sedimentary Geology, v. 383, p. 55–81, doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2019.01.006.

Lima, B. E. M., L. R. Tedeschi, A. L. S. Pestilho, R. V. Santos, J. C. Vazquez, J. V. P. Guzzo, and L. F. De Ros, 2020, Deep-burial hydrothermal alteration of the PreSalt carbonate reservoirs from northern Campos Basin, offshore Brazil: Evidence from petrography, fluid inclusions, Sr, C and O isotopes: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 113, no. 2020, 104143, 25 p., doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104143.

Lønøy, A., 2006, Making sense of carbonate pore systems: AAPG Bulletin, v. 90, no. 9, p. 1381–1405, doi:10.1306/03130605104.

Matheus, G. F., M. Basso, J. P. P. Souza, and A. C. Vidal, 2023, Digital rock analysis based on x-ray computed tomography of a complex pre-salt carbonate reservoir from the Santos Basin, SE Brazil: Transport in Porous Media, v. 150, no. 1, p. 15–44, doi:10.1007/s11242-023-01986-6.

Mazzullo, S. J., and G. V. Chilingarian, 1992, Diagenesis and origin of porosity, in G. V. Chilingarian, S. J. Mazzullo, and H. H. Rieke, eds., Carbonate reservoir characterization: A geologic-engineering analysis, part I, 1st ed., v. 30: Amsterdam, Elsevier, pp. 199–270.

Mohriak, W. U., 2003, Bacias sedimentares da margem continental Brasileira: Geologia, Tectônica e Recursos Minerais Do Brasil, v. 3, p. 87–165.

Mohriak, W. U., P. Szatmari, and S. Anjos, 2012, Salt: Geology and tectonics of selected Brazilian basins in their global context, in G. I. Alsop, S. G. Archer, A. J. Hartley, N. T. Grant, and R. Hodgkinson, eds., Salt tectonics, sediments and prospectivity: Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2012, v. 363, p. 131–158.

Moreira, J. L. P., C. V. Madeira, J. A. Gil, and M. A. P. Machado, 2007, Bacia de Santos: Boletim De Geociências Da Petrobras, v. 15, no. 2, p. 531–549.

Pentecost, A., 1990, The formation of travertine shrubs: Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyoming: Geological Magazine, v. 127, no. 2, p. 159–168, doi:10.1017/S0016756800013844.

Pereira, M. J., and F. J. Feijó, 1994, Bacia de Santos: Boletim De Geociências Da Petrobras, Rio De Janeiro, v. 8 no. 1, p. 219–234.

Rezende, M. F., S. N. Tonietto, and M. C. Pope, 2013, Three-dimensional pore connectivity evaluation in a Holocene and Jurassic microbialite buildup: AAPG Bulletin, v. 97, no. 11, p. 2085–2101, doi:10.1306/05141312171.

Riding, R., 2008, Abiogenic, microbial and hybrid authigenic carbonate crusts: Components of Precambrian stromatolites: Geologia Croatica, v. 61, no. 2–3, p. 73–103, doi:10.4154/GC.2008.10.

Rodríguez-Berriguete, Á., P. F. Dal’ Bo, B. Valle, and L. Borghi, 2022, When distinction matters: Carbonate shrubs from the Aptian Barra Velha Formation of Brazilian’s Pre-salt: Sedimentary Geology, v. 440, 106236, 15 p., doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2022.106236.

Saller, A., S. Rushton, L. Buambua, K. Inman, R. Mcneil, and J. A. D. Dickson, 2016, Pre-salt stratigraphy and depositional systems in the Kwanza Basin: Offshore Angola: AAPG Bulletin, v. 100, p. 1135–1164, doi:10.1306/02111615216.

Schrank, A. B. S., T. Dos Santos, S. D. Altenhofen, W. Freitas, E. Cembrani, T. Haubert, F. Dalla Vecchia, , 2024, Interactions between clays and carbonates in the Aptian Pre-salt reservoirs of Santos Basin, eastern Brazilian margin: Minerals, v. 14, no. 2, 191, 35 p., doi:10.3390/min14020191.

Silva, M. D., M. E. B. Gomes, A. S. Mexias, M. Pozo, S. M. Drago, R. S. Célia, L. A. C. Silva, , 2022, Mineralogical study of levels with magnesian clay minerals in the Santos Basin, Aptian pre-salt Brazil: Minerals, v. 11, 970, 19 p., doi:10.3390/min11090970.

Strugale, M., B. E. M. Lima, C. Day, J. Omma, J. Rushton, J. P. R. Olivito, J. Bouch, L. Robb, N. Roberts, and J. Cartwright, 2024, Diagenetic products, settings and evolution of the pre-salt succession in the Northern Campos Basin, Brazil, in J. Garland, A. J. Barnett, T. P. Burchette, and V. P. Wright, eds., Carbonate reservoirs: Applying current knowledge to future energy needs: Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2024, v. 548, p. 231–265, doi:10.1144/SP548-2023-93.

Tamoto, H., A. L. S. Pestilho, and A. M. B. Rumbelsperger, 2024, Impacts of diagenetic processes on petrophysical characteristics of the Aptian presalt carbonates of the Santos Basin, Brazil: AAPG Bulletin, v. 108, no. 1, p. 75–105, doi:10.1306/05302322046.

Teboul, P. A., J. M. Kluska, N. C. M. Marty, M. Debure, C. Durlet, A. Virgone, and E. C. Gaucher, 2017, Volcanic rock alterations of the Kwanza Basin, offshore Angola—Insights from an integrated petrological, geochemical, and numerical approach: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 80, p. 394–411, doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2016.12.020.

Terra, G. J. S., A. R. Spadini, A. B. França, C. L. Sombra, E. E. Zambonato, L. C. S. Juschaks, L. M. Arienti, , 2010, Classificação de rochas carbonáticas aplicável às bacias sedimentares brasileiras: Boletim Geociências Petrobras, v. 18, p. 9–29.

Tosca, N. J., and V. P. Wright, 2015, Diagenetic pathways linked to labile Mg-clays in lacustrine carbonate reservoirs: A model for the origin of secondary porosity in the Cretaceous pre-salt Barra Velha Formation, offshore Brazil: Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2015, v. 435, p. 33–46.

Vieira de Luca, P. H., H. Matias, J. Carballo, D. Sineva, G. A. Pimentel, J. Tritlla, M. Esteban, , 2017, Breaking barriers and paradigms in presalt exploration: The Pão de Açúcar discovery (offshore Brazil), in R. K. Merrill and C. A. Sternbach, eds., Giant fields of the decade 2000–2010: AAPG Memoir 113, p. 177–194.

Wang, Q., M. Tan, C. Xiao, S. Wang, C. Han, and L. Zhang, 2022, Pore-scale electrical numerical simulation and new saturation model of fractured tight sandstone: AAPG Bulletin, v. 106, no. 7, p. 1479–1497, doi:10.1306/04132220165.

Warren, J. K., 2006, Karst, breccia, nodules and cement: Pointers to vanished evaporites, in Evaporites: Sediments, resources and hydrocarbons: Cham, Switzerland, Springer, p. 455–566.

Weger, R. J., G. P. Eberli, G. T. Baechle, J. L. Massaferro, and Y.-F. Sun, 2009, Quantification of pore structure and its effect on sonic velocity and permeability in carbonates: AAPG Bulletin, v. 93, no. 10, p. 1297–1317, doi:10.1306/05270909001.

Wennberg, O. P., G. McQueen, P. H. Vieira de Luca, F. Lapponi, D. Hunt, A. S. Chandler, A. Waldum, G. N. Camargo, E. Castro, and L. Loures, 2021, Open fractures in pre-salt silicified carbonate reservoirs in block BM-C-33, the Outer Campos Basin, offshore Brazil: Petroleum Geoscience, v. 27, no. 4, 16 p., doi:10.1144/petgeo2020-125.